Navigation

Table of Contents

Preliminary Matters

CAFC clarifies standing rules when appealing PTAB decisions

In Platinum Optics Tech. v. Viavi Solutions: Standing, 1), the Federal Circuit held that a party does not need Article III standing to appear before an administrative agency, but standing is required once the party seeks review of an agency's final action in a federal court.

Holdings:

- “To establish a case or controversy, the appellant must meet the irreducible constitutional minimum of standing. This requires that the appellant: (1) suffered an injury in fact, (2) that is fairly traceable to the challenged conduct of the defendant, and (3) that is likely to be redressed by a favorable judicial decision.

- “Where a party relies on potential infringement liability as a basis for standing, the party “must establish that it has concrete plans for future activity that creates a substantial risk of future infringement or will like cause the patentee to assert a claim of infringement.”

- PTOT's unsubstantiated speculation about a threat of future suit [based in part on a letter dated prior to an earlier infringement action that was dismissed with prejudice] is insufficient to show a substantial risk of future infringement or that Viavi is likely to assert a claim against it for the continued distribution of bandpass filters accused in Viavi II. Therefore PTOT has not established an injury in fact.

- “Of course, IPR petitioners need not concede infringement to establish standing to appeal. But [Director of Operation Management at PTOT] Lin's vague and conclusory statements are insufficient to establish that PTOT has concrete plans for the development of bandpass filters. [. . .] Lin states that 'PTOT anticipates that Viavi will assert the '369 patent against PTOT's bandpass filters currently under development in the same way that Viavi has sued PTOT on its prior bandpass filters.' Lin's contentions, however, do not pass muster to establish there is a substantial risk of a future infringement suit.

Fed. Cir. finds foreign defendants cannot avoid personal jurisdiction in one venue by consenting to personal jurisdiction in another (posted 01/16/23)

FCRP 4(k)(2): Federal Claim Outside State-Court Jurisdiction. For a claim that arises under federal law, serving a summons or filing a waiver of service establishes personal jurisdiction over a defendant if:

(A) the defendant is not subject to jurisdiction in any state’s courts of general jurisdiction; and

(B) exercising jurisdiction is consistent with the United States Constitution and laws.

In a narrow precedential ruling, the Federal Circuit, in In re: Stingray IP Solutions, granted Singray IP's petition for a writ of mandamus seeking to reverse the district in the eastern district of Texas to central California. Stated the court:

Stingray’s petition focuses on the so-called “negation requirement” of Rule 4(k)(2)(A)—that “the defendant is not subject to jurisdiction in any state’s courts of general jurisdiction.” More specifically, Stingray’s petition presents the question of whether a defendant’s post-suit, unilateral consent to suit in another state prevents this condition from being satisfied. In addressing this issue, we do not write on a clean slate.

[. . .]

Therefore, we now confirm that “the defendant’s burden under the negation requirement entails identifying a forum where the plaintiff could have brought suit—a forum where jurisdiction would have been proper at the time of filing, regardless of consent.” A defendant (such as TP-Link) cannot simply use a “unilateral statement of consent” to preclude application of Rule 4(k)(2) and “achieve transfer into a forum it considers more convenient (or less convenient for its opponent).”

Citations omitted.

No bright-line rule for minimum contacts giving rise to personal jurisdiction (posted 04/19/22)

In Apple Inc. v. Zipit Wireless, Inc., the Federal Circuit reversed a N.D. California court judge who held that it did not have personal jurisdiction over Zipit despite “minimum contacts” including “multiple letters and claim charts accusing Apple of patent infringement” and the fact that agents for Zipit traveled to Apple's offices in California to discuss these accusations. The district court held that, despite these minimum contacts, it was bound by precedent Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewics 2) which held that “the exercise of personal jurisdiction . . . would be unconstitutional when all of the contacts were for the purpose of warning against infringement or negotiating license agreements, and the defendant lacked a binding obligation in the forum” (internal quotations, citations omitted).

On review, the Federal Circuit reversed, stating (citations omitted, some alteration):

“Zipit argues that minimum contacts are not satisfied here, relying principally on this court’s decision in Autogenomics. In Autogenomics, the defendant-patentee sent a notice letter to the declaratory-judgment plaintiff, the plaintiff “expressed interest in taking a license,” and two of the patentee’s representatives flew to California (the forum state) to meet with the plaintiff’s representatives. Based on the facts of the case and the nature of the specific communications at hand, we determined that the plaintiff “failed to allege sufficient activities ‘relat[ing] to the validity and enforceability of the patent’ in addition to the cease-and-desist communications” to demonstrate minimum contacts.

Zipit argues (and Apple suggested) that Autogenomics created a “bright-line rule . . . that cease-and-desist letters and related in-person discussions cannot support [minimum contracts for] personal jurisdiction.” Appellee’s As an initial matter, we note that there are material factual distinctions between Autogenomics and this case.3 More importantly though, our precedent as a whole—including decisions both before and after Autogenomics—supports our determination that minimum contacts are satisfied here.

Fed. Cir.: Exclusive licensee lacks standing to sue (09/23/21)

Oral Hearing - enhanced audio

In In re Cirba, Inc., the Federal Circuit ruled on the petition for writ of mandamus that Cirba Inc. lacked rights under its exclusive licensee contract from Cirba IP to enforce the patents. The court also rejected Cirba's argument that “it is sufficient for Article III standing that a party demonstrate a concrete injury traceable to the challenged conduct.” On this point, the court clarified it's interpretation of the Supreme Court's holding in Lexmark 3) stating that ”[i]t is not clear, however, that Lexmark and Lone Star also require us to alter our precedent holding . . . that 'the touchstone of constitutional standing in a patent infringement case is whether a party can establish that it has an exclusionary right in a patent that, if violated by another, would cause the party holding the exclusionary right to suffer legal injury.'”

Fed. Cir. denies standing to non-licensee (09/22/07)

In Morrow v. Microsoft, 4) the Fed. Cir. upheld the district court's ruling in favor of a motion for summary judgment filed by Microsoft that Morrow lacked standing to sue Microsoft on behalf of the General Unsecured Creditors' Liquidating Trust (GUCLT) because the GUCLT was assigned only the rights to sue under a bankruptcy settlement, not the patent title or an exclusive license. Stated the court: “The problem for GUCLT and AHLT [the patent holder] is that the exclusionary rights have been separated from the right to sue for infringement. The liquidation plan contractually separated the right to sue from the underlying legally protected interests created by the patent statutes—the right to exclude.”

Judge Prost dissents: “I agree with the majority insofar as it holds that GUCLT does not have standing to enforce the patent in its own name. . . . But the analysis does not end there. As it is apparent that AHLT, having assigned the right to sue, cannot enforce the patent alone, the only way to enforce the patent requires AHLT and GUCLT to act as co-plaintiffs. The majority opinion forecloses that option.”

- Note: The opinion also provides, in dicta, a concise explanation of standing requirements for different categories of plaintiffs.

Nov. 16 – Petition for rehearing en banc denied by Fed. Cir.

An unremarkable Fed. Cir. Decision (09/09/07)

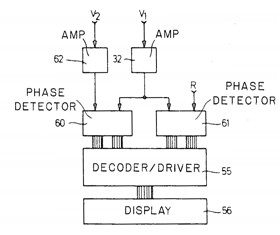

In Mitutoyo Corp. et al. v. Central Purchasing, Central Purchasing appeals the district court ruling that Central Purchasing infringed U.S. Patent 4,743,902 in contravention of a 1994 settlement agreement between the parties. On the issue of standing, the Fed. Cir. upheld the lower court ruling that co-plaintif Mitutoyo America Corp (“MAC”) lacked standing because MAC lacked the exclusive rights to sell in the United States under the '902 patent. Read more about this case on the issues of claim construction, willfulness, and ordinary damages.

In Mitutoyo Corp. et al. v. Central Purchasing, Central Purchasing appeals the district court ruling that Central Purchasing infringed U.S. Patent 4,743,902 in contravention of a 1994 settlement agreement between the parties. On the issue of standing, the Fed. Cir. upheld the lower court ruling that co-plaintif Mitutoyo America Corp (“MAC”) lacked standing because MAC lacked the exclusive rights to sell in the United States under the '902 patent. Read more about this case on the issues of claim construction, willfulness, and ordinary damages.

Asserting patent rights leads to case or controversy (11/14/07)

In Sony Electronics & Mitsubishi Digital Electronics America & Thomson & Victor Company of Japan & Matsushita Electric Industrial v. Guardian Media Technologies, the Fed. Cir. reversed the district court's dismissal of a declaratory judgment action brought by Sony et al. for lacking subject matter jurisdiction due to a lack of a “case or controversy.” Sony argued that letters it received letters from Guardian, including detailed claim charts comparing the patent claims with representative Sony products, gave rise to a reasonable apprehension of being sued. Prior to Sony's filing of the complaint, the parties had adverse positions as to whether infringement of valid claims occurred. The fact that Guardian was at all times willing to negotiate a “business resolution” does not impact the determination as to whether a case or controversy existed. Sony was within its rights to terminate the business negotiations when it determined that further negotiations would be unproductive. Relying on MedImmune 5), The Fed. Cir. stated that a declaratory judgment plaintiff does not need to establish “reasonable apprehension” of a lawsuit, and that the facts are sufficient to show an actual controversy between Sony and Guardian, the dispute being “definite and concrete, touching the legal relations of parties having adverse legal interests” (quoting Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Releasomers, Inc. 6).

More on standing: Substantial controversy in generic drugs (04/04/07)

In Teva v. Novartis, the Teva filed an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) with the FDA, which may have been a sufficient act to precipitate a substantial controversy over infringement of Novartis' patents related to the drug.

Fed Cir. opens floodgates: Substantial controversy supplants reasonable apprehension (03/29/07)

In SanDisk v. STMicroelectronics, the Fed. Cir., citing MedImmune 7), found that SanDisk had standing to sue for declaratory judgment after being presented a claim chart mapping claims of a patent owned by STMicroelectronics to SanDisk's technology in the context of cross-licensing negotiations. There was no need for SanDisk to break off licensing negotiations before suing for declaratory judgmenet. In dicta, the court noted that ”[T]o avoid the risk of a declaratory judgment action, ST could have sought SanDisk’s agreement to the terms of a suitable confidentiality agreement.” The rule adopted by the court that standing to sue for declaratory judgment exists where a pantetee seeks a right to a royalty based on specific identified acts committed by the accused infringer. Judge Bryson noted in a concurring opinion that “it would appear that under the court’s standard virtually any invitation to take a paid license relating to the prospective licensee’s activities would give rise to an Article III case or controversy if the prospective licensee elects to assert that its conduct does not fall within the scope of the patent.”

- Summary and analysis

Supreme Ct. Rules gives standing to licensee (01/17/07)

The Supreme Court's ruling in MediImmune v. Genentech has garnered a lot of attention by the press and bloggers. Under certain circumstances, a licensee can now challenge the validity of the patent it is licensing without first repudiating the contract.