Navigation

Table of Contents

Determining Damages

Damages expert falsely identifies asserted patents as key; new trial ordered. (posted 03/08/22)

In Apple v. Wi-LAN, the Federal Circuit held that the lower court abused its discretion by denying Apple's motion for a new trial because plaintiff's damages expert testimony by Mr. Kennedy, was flawed. The expert stated that the '145 and '757 patents asserted in this trial were “key patents” because (1) they were specifically listed in the comparable licenses, (2) they were discussed in negotiations, and (3) Apple continued to use the technology after the patents were asserted against them rather than switch to a non-infringing alternative. However, the court disagreed, stating that “Mr. Kennedy’s opinion that the asserted patents were key patents is untethered to the facts of this case” and cited evidence of the untruths stated by Mr. Kennedy. The court concluded, “Mr. Kennedy’s methodological and factual errors in analyzing the comparable license agreements render his opinion untethered to the facts of this case. Thus, Mr. Kennedy’s damages testimony should have been excluded. We conclude that the district court abused its discretion in denying Apple's motion for a new trial on damages.”

SCOTUS reversed Fed. Cir. on extraterritoriality of lost profits (updated 06/25/18)

35 U.S.C. § 271(f)(1): Whoever without authority supplies or causes to be supplied in or from the United States all or a substantial portion of the components of a patented invention, where such components are combined in whole or in part, in such manner as to actively induce the combination of such components outside of the United States in a manner that would infringe the patent if such combination occurred within the United States, shall be liable as an infringer.

35 U.S.C. § 271(f)(2): Whoever without authority supplies or causes to be supplied in or from the United States or any component of a patented invention that is especially made or especially adapted for use in the invention and not a staple article or commodity of commerce suitable for substantial noninfringing use, where such component is uncombined in whole or in part, knowing that such component is so made or adapted and intending that such component will be combined outside of the United States in a manner that would infringe the patent if such combination occurred within the United States, shall be liable as an infringer.

35 U.S.C. 284 ¶1: Upon finding for the claimant the court shall award the claimant damages adequate to compensate for the infringement but in no event less than a reasonable royalty for the use made of the invention by the infringer, together with interest and costs as fixed by the court.

On June 22, 2018, the Supreme Court held, in WesternGeco v. Ion Geophysical Corp., that WesternGeco is entitled to lost profit damages it sustained by infringement of its patents on the high seas by defendant ION Geophysical. This case impacts on how lost profits damages are calculated when infringement within the U.S. results in lost profits abroad.

Stated the Court (Justice Thomas)(quoting, with internal quotes and citations removed, some rearrangement for clairty):

- The Court has established a two-step framework for deciding questions of externality. The first step asks “whether the presumption against extraterritoriality has been rebutted.”

- While it will usually be preferable to begin with step one, courts have the discretion to begin at step two in appropriate cases. [. . .] WesternGeco argues that the presumption against extraterritoriality should never apply to statutes, such as § 284, that merely provide a general damages remedy for conduct that Congress has declared unlawful. Resolving that question could implicate other statutes besides the Patent Act. We therefore exercise our discretion to forgo the first step of our extraterritoriality framework.

- . . . the second step . . . asks whether the case involves a domestic application of the statute. Under [this step], we must identify the statute's focus. The focus of a statute . . . can include the conduct it seeks to regulate, as well as the parties and interests it seeks to protect or vindicate. If the conduct relevant to the statute's focus occurred in the United States, then the case involves a permissible domestic application of the statute, even if other conduct occurred abroad. But if the relevant conduct occurred in another country, then the case involves an impermissible extraterritorial application regardless of any other conduct that occurred in the U.S. territory.

- Applying these principles here, we conclude that the conduct relevant to the statutory focus in this case is domestic. We begin with §284. It provides a general damages remedy for the various types of patent infringement identified in the Patent Act. The portion of §284 at issue here states that “the court shall award the claimant damages adequate to compensate for the infringement.” [. . .] The question posed by the statute is how much has the Patent Holder suffered by the infringement. Accordingly, the infringement is plainly the focus of §284. But that observation does not fully resolve this case. . . . We thus turn to §271(f)(2), which was the basis for WesternGeco's infringement claim and the lost-profits damages that it received.

- The conduct that §274(f)(2) regulates—i.e., its focus—is the domestic act of “suppl[ying] in or from the United States.” [. . .] The conduct in this case that is relevant to that focus clearly occurred in the United States, as it was ION's domestic act of supplying the components that infringed WesternGeco's patents. Thus, the lost-profits damages that were awarded to WesternGeco were a domestic application of §284.

Justice Gorsuch, joined by Breyer, dissented, stating:

- A U.S. Patent provides a lawful monopoly over the manufacture, use, and sale of an invention within this country only. Meanwhile, WesternGeco seeks lost profits for uses of its invention beyond our borders. WesternGeco assumes it could have charged monopoly rents abroad premised on a U.S. patent that has no legal force there. Permitting damages of this sort would effectively allow U.S. patent owners to use American courts to extend their monopolies to foreign markets. That, in turn, would invite other countries to use their patent laws and courts to assert control over our economy. Nothing in the terms of the Patent Act supports that result and much militates against it.

Background

In July of 2015, the Federal Circuit reversed a $93 million jury award to patent owner WesternGeco for lost profits, keeping in place the $12.5 million reasonable royalty award. The patents are directed to technologies for detecting subsurface geology, useful for searching for oil and gas beneath the ocean floor. ION, manufactures patent-infringing “DigiFIN” devices and sells them to customers overseas, who perform surveys on behalf of oil companies.

Patent holder WesternGeco identified contracts for ten surveys collectively worth over $90 million in profit that they would have won the contract for but for their competition having access to the DigiFIN products. However, WesternGeco did not contend that the contracts were entered into within the United States, and they were all performed on the high seas outside the jurisdictional reach of U.S. patent law.

Quoting the prior decision, Power Integrations, Inc. v. Fairchild Semiconductor Int'l, Inc.,1) the court stated that, “[o]ur patent laws do not thereby provide compensation for a defendant's foreign exploitation of a patented invention, which is not infringement at all.” The court held:

Under Power Integrations, WesternGeco cannot recover lost profits resulting from its failure to win foreign service contracts, the failure of which allegedly resulted from ION's supplying infringing products to WesternGeco's competitors.

J. Wallace dissented, saying that “the patent statute requires consideration of [lost foreign] sales as part of the damages calculation. . . .”

In September, 2016, the Federal Circuit again considered this case on remand from the Supreme Court to reconsider willful damages in light of the recent Halo Electronics ruling.

At the Supreme Court

On January 12, 2018, the Supreme Court granted WesternGeco's petition for writ of certiorari with the question being: Whether a patent owner that has proved a domestic act of infringement may recover lost profits that the patentee would have earned outside the United States if that domestic infringement had not occurred.

Amicus Briefs

Since then we've seen a number of amicus briefs. Here is a representative sampling:

- The United States Solicitor General of the Department of Justice: Relying on the presumption against extraterritorial application of U.S. law, the court construed 35 U.S.C. 284 not to authorize recovery of profits that petitioner would have earned on the high seas. That holding is inconsistent with the text and purpose of Section 284.

- IPLA of Chicago: The Federal Circuit “deprived the Petitioner of its lawful remedy by incorrectly finding that to do so would require extraterritorial application of U.S. patent law.”

- IPO: Construing § 284 as per se barring compensation for the lost profits from foreign sales frustrates the congressional intent behind § 271(f) and diminishes the incentive for innovation offered by patent protection.

- Scholars in support of neither party: The court should (1) conclude that the presumption applies to remedial provisions, (2) require formal consideration of comity and potential conflicts with foreign law before allowing an award of damages arising outside the United States, and (2) the presumption against extraterritoriality should be considered as part of the proximate cause analysis when determining whether the asserted damages are appropriate.

Oral Arguments (posted 04/18/18)

Blogs

Supreme Court nixes Seagate, relaxes treble damages rule (posted 06/14/16)

35 U.S.C. § 284:

Upon finding for the claimant the court shall award the claimant damages adequate to compensate for the infringement but in no event less than a reasonable royalty for the use made of the invention by the infringer, together with interest and costs as fixed by the court.

When the damages are not found by a jury, the court shall assess them. In either event the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed. Increased damages under this paragraph shall not apply to provisional rights under section 154(d) .

The court may receive expert testimony as an aid to the determination of damages or of what royalty would be reasonable under the circumstances.

In a combined ruling for Halo Electronics v. Pulse Electronics2) and Stryker v. Zimmer, the Supreme Court struck down the two-part test under In re Seagate technology, LLC, 3) for determining when a district court may increase patent infringement damages under 35 U.S.C. § 284.

Holdings

Stated the court:

- [Section 284] contains no explicit limit or condition, and we have emphasized that the “word 'may' clearly connotes discretion” [citing Martin v. Franklin Capital Corp.]] [. . .] At the same time, “[d]iscretion is not a whim.” . . . Thus, although there is “no precise rule or formula” for awarding damages under §284, a district court's “discretion should be exercised in light of the considerations” underlying the grant of that discretion. [Internal citations removed.]

- That [Seagate]] test . . . “is unduly rigid, and it impermissibly encumbers that statutory grant of discretion to district courts” [quoting Octane Fitness]. In particular, it can have the effect of insulating some of the worst patent infringers from any liability for enhanced damages.

- The principle problem with Seagate's two-part test is that it requires a finding of objective recklessness in every case before the district courts may award enhanced damages. [. . .] The existence of such a defense insulates the infringer from enhanced damages, even if he did not act on the basis of the defense or was even aware of it. Under that standard, someone who plunders a patent–infringing it without any reason to suppose his conduct is arguably defensible–can nevertheless escape any comeuppance under §284 solely on the strength of his attorney's ingenuity.

- Section 284 allows district courts to punish the full range of culpable behavior. Yet none of this is to say that enhanced damages must follow a finding of egregious misconduct. As with any exercise of discretion, courts should continue to take into account the particular circumstances of each case in deciding whether to award damages, and in what amount. Section 284 permits district courts to exercise their discretion in a manner free from the inelastic constraints of the Seagate test. Consistent with nearly two centuries of enhanced damages under patent law, however, such punishment should generally be reserved for egregious cases typified by willful misconduct [emphasis added].

- The Seagate test is also inconsistent with §284 because it requires clear and convincing evidence to prove recklessness. [. . .] Like §285, §284 “imposes no specific evidentiary burden, much less such a high one” [quoting Octane]. [. . .] As we explained in Octane Fitness, “patent-infringement litigation has always been governed by a preponderance of the evidence standard.” [. . .] Enhanced damages are no exception.

- Finally . . . we . . . reject the Federal Circuit's tripartite framework for appellate review. [. . .] Because Octane Fitness confirmed district court discretion to award attorney fees, we concluded that such decisions should be reviewed for abuse of discretion. [. . .] The same conclusion follows naturally from our holding here.

Concurring opinion by Justice Breyer, joined by Kennedy and Alito

Stated J. Breyer:

- First, the Court's references to “willful misconduct” do not mean that a court may award enhanced damages simply because the evidence shows that the infringer knew about the patent and nothing more. [. . .] Here, the court's opinion, read as a whole and in context, explains that “enhanced damages are generally appropriate . . . only in egregious cases.” [. . .] They amount to “punitive” sanction for engaging in conduct that is either “deliberate” or “wanton.”

- Second, the Court writes against a statutory background specifying that the “failure of an infringer to obtain the advice of counsel . . . may not be used to prove that the accused infringer willfully infringed.” §298. The Court does not weaken this rule through its interpretation of § 284. Nor should it.

- Third, . . . enhanced damages may not “serve to compensate patentees” for infringement-related costs or litigation expenses. [. . .] That is because §283 provides for the former prior to any enhancement.

- Consider that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office estimates that more than 2,500,000 patents are currently in force. [. . .] moreover, Members of the Court have noted that some “firms use patents . . . primarily [to] obtai[n] licensing fees” [citing eBay]. Amici explain that some of those firms generate revenue by sending letters to “tens of thousands of people asking for a license or settlement” on a patent “that may in fact not be warranted.” [. . .] How is a growing business to react to the arrival of such a letter, particularly if that letter carries with it a serious risk of treble damages? Does the letter put the company “on notice” of the patent? Will a jury find that the company behaved “recklessly” simply for failing to spend considerable time, effort, and money obtaining expert views about whether some or all of the patents described in the letter apply to its activities (and whether the patents are even valid)? These investigative activities can be costly. Hence the risk of treble damages can encourage the company to settle, or even abandon any challenged activity. [¶] To say this is to point to a risk: The more that businesses . . . adopt this approach, the more often a patent will reach beyond its lawful scope to discourage lawful activity, and the more often patent-related demands will frustrate, rather than “promote” the “Progress of Science and useful Arts” [quoting Art. I, §8, cl. 8 of the Constitution]. [. . .] Thus, in the context of enhanced damages, there are patent-related risks on both sides of the equation. That fact argues, not for abandonment of enhanced damages, but for their careful application, to ensure that they only target cases of egregious misconduct.

- [Editor's note: Is Breyer saying that ignoring threads from patent trolls should not be considered “egregious”?]

- One final point: The Court holds that awards of enhancement damages should be reviewed for an abuse of discretion. [. . .] I agree. But I also believe that, in applying that standard, the Federal Circuit may take advantage of its own experience in patent law. Whether, for example, an infringer truly had “no doubts about [the] validity” of a patent may require an assessment of the reasonableness of a defense that may be apparent from the face of that patent.

Read more

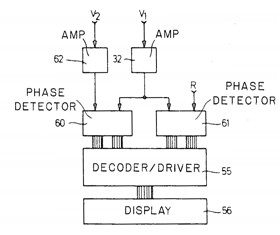

An unremarkable Fed. Cir. Decision (09/09/07)

In Mitutoyo Corp. et al. v. Central Purchasing, Central Purchasing appeals the district court ruling that Central Purchasing infringed U.S. Patent 4,743,902 in contravention of a 1994 settlement agreement between the parties. On the issue ordinary damages, the Fed. Cir. approved of the lower court's denial of lost profit damages and the reasonable royalty, but remanded on the royalty base, which improperly included a non-party's sales, despite the business relationship between the defendant and the non-party. Read more about this case on the issues of claim construction, willfulness, and standing.

In Mitutoyo Corp. et al. v. Central Purchasing, Central Purchasing appeals the district court ruling that Central Purchasing infringed U.S. Patent 4,743,902 in contravention of a 1994 settlement agreement between the parties. On the issue ordinary damages, the Fed. Cir. approved of the lower court's denial of lost profit damages and the reasonable royalty, but remanded on the royalty base, which improperly included a non-party's sales, despite the business relationship between the defendant and the non-party. Read more about this case on the issues of claim construction, willfulness, and standing.

Rambus' damages in jeopardy (07/20/06)

The jury awarded Rambus Inc. (“Rambus”) damages in the amount of $306,967,272 in the patent phase of this trial. In a decision by the U.S. District court for the Northern District of California, Hynix's motion for a new trial on the issue of damages is GRANTED unless Rambus files notice with the court within thirty (30) days of this order accepting remittur of the jury award to $133,584,129 for damages through December 31, 2005.

- Hynix argued (1) rates in comparable licensing agreements reflected an uncertainty discount; (2) a hypothetical negotiation required consideration of only United States sales as opposed to comparable licensing agreements which were based upon worldwide sales; (3) comparable licensing agreements included up-front fees in addition to the running royalty rates; and (4) a published survey indicated higher royalty rates are commanded by revolutionary technologies.

35 U.S.C. § 287(a) enforced: Mark your websites (07/05/06)

In IMX, Inc. v. LendingTree, LLC, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 33179 (D. Del. Dec. 14, 2005); motion for reconsideration denied, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 551 (D. Del. Jan. 10, 2006), the court ruled that, because no “patented” notice was present on IMX's web site, which facilitated downloading of patented software, IMX's damages were limited to those accruing from the date of filing of the action.

The Supreme Court held oral arguments on April 16, 2018.

The Supreme Court held oral arguments on April 16, 2018.