Table of Contents

Claim Construction

Terms defined in family patents incorporated by reference cannot modify claim scope (posted 11/07/22)

In Finjan LLC v. ESET, LLC, the Federal Circuit reversed a lower court holding that interpreted the term, “Downloadables” as requiring that the “downloadable” portion of a program be “small” because nonasserted patents that were incorporated by reference into asserted patents mention “small” in their definition of “downloadable.” Without any explanation of what the limits of “small” is, the lower court granted a summary judgment invalidity motion requesting the court declare the claim to be indefinite.

The Fed. Cir. reversed, stating that when a first patent is incorporated by reference into a second (“host”) patent, the invention claimed in the first patent does not become part of or otherwise change the invention claimed in the second. Rather, the first patent's disclosure serves to inform the construction of claim terms that are also found in the host patent. Stated the court, it is “erroneous to assume that the scope of the invention is the same such that disclaimers of scope necessarily apply across patents.”

"Resilient" and "pliable" are broad, not indefinite (posted 04/12/22)

In Niazi Licensing Corp. v. St. Jude Medical S.C., Inc., the Federal Circuit, in a precedential ruling, found that claims directed to a two-part extensible catheter having “an outer, resilient catheter” and “an inner, pliable catheter” were not indefinite. Stated the court:

“[D]escriptive words (or terms of degree) in a claim may inherently result in broader claim scope. . . . But a claim is not indefinite just because it is broad. For purposes of the definiteness inqury, the problem patentees face by using descriptive words in their claims is not the potential breadth of those claims. It is whether the use of descriptive phrasing in the claim results in a claim that 'fail[s] to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention.'

The court explored its history in this space, addressing:

- Sonix Technologies: “visually negligible” provided an objective baseline through which to interpret the claims – whether it could be seen by the normal human eye. In other words, it was not a “purely subjective” phrase.

- Enzo Biochem, Inc. v. Applera Corp.: “not interfacing substantially” was not indefinite because the linkage group in a chemical compound was “not interfering substantially” with the ability of the compound to hybridize with nucleic acid. The intrinsic evidence provided guideposts for a skilled artisan to determine the scope of the claims, including dependent claims with exemplary linkage groups.

- Datamize, LLC v. Plumtree Software, Inc.: “aesthetically pleasing” was indefinite because the scope of the claim changed depending on a person's subjective determination as to whether the interface screen was “aesthetically pleasing.” “While beauty is in the eye of the beholder, a claim term, to be definite, requires an objective anchor.”

- Intellectual Ventures I, LLC v. T-Mobile USA, Inc.: “QoS requirements” was held to be “purely subjective” because (1) the patent described “QoS requirements” as “defined by what network performance characteristic is most important to the particular user” and (2) the patent further characterized it as “a relative term, finding different meanings for different users.”

The court concluded that “the intrinsic record is sufficient to dispose of the indefiniteness issues as to the terms 'resilient' and 'plaible.' [. . .] We also note that extrinsic evidence further supports our conclusion. Niazi introduced dictionary definitions of both terms to demonstrate that the claims are not indefinite.”

Expert's opinion on proc. history estoppel improperly extended "clear disavowal" (posted 04/04/22)

In Genuine Enabling Technology LLC v. Nintendo, the Federal Circuit reversed a district court's ruling on Summary Judgment for Nintendo, holding that prosecution history estoppel should be limited to “clear disavowal” and that expert opinion thereof should not “diverge significantly from the intrinsic record.”

Fed. Cir. reverses lower court's importation into claims of structure described in spec. (posted 03/07/22)

In Clifford A. Lowe et al. v. Shieldmark, Inc., et al., the Federal Circuit reversed a lower court summary judgment of non-infringement, concluding that the lower court erred in its claim construction.

The district court construed the term “lateral edge portion” to mean “the portion of the floor marking tape from the shoulder to the edge of the tape when viewed in cross section.” (emphasis added). The court acknowledged that “the term ‘shoulder’ is not present in the ’664 [p]atent[] claims,” but explained that it “appears repeatedly in the patent [s]pecification[].”

In addition, the district court construed the limitation “the lower surface of each lateral edge portion being a flat coplanar extension of the lower surface of the body” to mean “a planar relationship exists between two or more things [that] does not allow the entire lower surface of the tape body to be one flat or planar surface.” (emphasis added) (internal quotation marks omitted). Again, in support of its construction, the court pointed out that the tape cannot have a flat lower surface because the specification repeatedly describes “a [l]ower surface 24 [that] defines a recess 30 bounded by a pair of shoulders 32.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with Lowe that the court erroneously imported the term “shoulder” from the specification into the claim language, that the shoulders are merely one embodiment. Stated the court:

”[The specification] states that tape with shoulders and a recess is just 'one embodiment' of the claimed invention. It further explains that '[o]ther structures combined with body 20 may also be used in place of . . . shoulders 32.' The specification goes on to describe additional 'embodiments' or 'configurations' of tape, several without shoulders.“

"Invention" in spec misconstrued by District Court (posted 01/18/22)

In Evolution Concepts v. HOC Events, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 01/14/22), the Federal Circuit reversed a Central District court for misconstruing “magazine catch bar,” which is a component for retaining a magazine in a magazine receiver in gun. The patent at issue is directed to an assembly for converting a gun having a removal magazine with one having a fixed magazine to reduce the rate of fire and regulatory burdens. The district court interpreted “magazine catch bar” as excluding an OEM magazine catch bar based on two separate pieces of evidence. First, an unasserted claim 15 requires removing “a magazine catch bar” and then installing “a magazine catch bar” suggesting that the one that is installed must be different from the one removed. Secondly, the specification states, “The invention is a permanent fixture added to a semi-automatic firearm by removing the standard OEM magazine catch assembly and installing the invention.”

The Federal Circuit disagreed stating that neither of the bases relied upon by the district court require that “magazine catch bar” be one other than an OEM magazine catch bar. With respect to claim 15, the court held that the “invention . . . involves removing and installing assemblies of parts–not only magazine catch bars” (emphasis in original). The court concludes: “The ordinary meaning of the claim language allows the factory-installed magazine catch bar to be removed as part of the initial assembly removal and reused as part of the assembly installed in a later step.” Finally, with respect to double-recitation of ”a magazine catch bar“ the court held that: “The inventors . . . did not choose to claim a device with a 'new' or 'different' magazine catch bar, but instead a device with ”a magazine catch bar” which, by its ordinary meaning, could be either the removed catch bar or a new or different catch bar.“

With respect to the language in the specification, the statement relied upon by the district court “has the same character as what is found in claim 15. . . . [T]he specification sentence does not preclude the installation of a factory-installed magazine catch bar.”

- News article (Paywall) (private cache)

PTAB slapped by Fed. Cir.: "analysis . . . falls short" (posted 08/03/20)

In Alacritech v. Intel Corp., the Federal Circuit found the PTAB's finding of invalidity based on obviousness was insufficiently supported in its ruling. Stated the court: “The Board's analysis fo the disclosure . . . falls short of that which the APA and our precedent require. [. . .] The Board's analysis does not acknowledge [the parties' dispute as to whether the prior art teaches packet reassembly on the NIC] much less explain how the prior art teaches or suggests reassembly in the network interface. As such we cannot reasonably discern whether the Board followed a proper path in determining that the asserted prior art teaches or suggests the reassembly limitations, and by extension that the subject matter . . . would have been obvious.” The primary reference 1) describes hardware off-load of packet reassembly but illustrates this alongside a NIC circuit.

Claim construction: “associating an operation code with said first packet” does not preclude association with a group of packets

Alacritech's argument that “associating an operation code” with a packet that indicates a status of the packet requires a direct mapping between one packet and one operation code. Alacritech provided no support for its interpretation beyond the language of the claims themselves. The court approved of the Board's rejection of this argument, stating that the plain claim language does not preclude an operation code from being associated with more than one packet, especially here where the broadest reasonable interpretation applies.

See also: Obviousness aspects of this ruling.

Fed. Cir. interprets claims in light of spec (posted 03/16/20)

In Personalized Media Communications, LLC, v. Apple, Inc., a three-judge panel of the Federal Circuit issued an opinion reversing PTAB and found that consistent statements by Applicant during prosecution “decisive” in interpreting claim limitations. A PTAB opinion, agreeing with Apple, held that, by plain meaning, an “encrypted digital information transmission including encrypted information” includes at least some encrypted digital information and does not preclude other non-encrypted information, and further found that “encrypting” can include analog scrambling. PTAB reasoned that the phrase, “including encrypted information” would be superfluous if the transmission did not also include non-encrypted information. Judge Stoll, writing for the Federal Circuit panel, noted that the specification did not expressly define “encrypted digital information transmission” but that it contemplates and discloses a number of mixed analog and digital embodiments consistent with PTAB's interpretation, and concludes that “evidence from the specification . . . fails to resolve the disputed claim term.” Agreeing with PMC, the panel held that several statements in the prosecution history clearly disclaim non-digital signal. The PTAB did not regard these statements as a clear waiver because “PMC's arguments to the examiner . . . did not 'clearly disavow mixed analog and digital information transmissions.” However, the panel held that, ”[e]ven where 'prosecution history statements do not rise to the level of unmistakable disavowal, they do inform the claim construction.'“

Fed Cir. judges disagree over "sessions" (posted 11/19/18)

6. A method for implementing a scaleable software crypto system between a main server and one or more agent servers communicating with one or more clients such that performance of the crypto system is increased to meet any demand comprising

providing a secure communication between the main server, agent server, and one or more clients such that communication between the main server and agent server enlists additional agent servers to support incremental secure sessions in response to maintaining performance at a desired level.

In Amazon.com v. ZitoVault, LLC, a divided Federal Circuit upheld the PTAB's construction for the term, “session” (in a computer networking context) and, consequently, the PTAB's finding of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. §103. Judge Prost dissented.

Writing for the majority, Judge Stoll first explained that under the broadest reasonable interpretation standard, which according to regulations is applied to to petitions filed before November 13, 2018, the court reviews the Board's legal determinations de novo and the Board's factual determinations for substantial evidence. The court stated that ”[u]nder the BRI standard, the Board's construction must be reasonable, that is, consistent with the record evidence and understanding of one skilled in the art. [. . .] Because the Board's construction comports with that standard, we affirm it.“ The Board held that the term “sessions” refers to “a set of transmitters and receivers, and the data streams that flow between them wherein each data stream flowing between the transmitters and receivers has a recognizable beginning of the data stream transmission and a recognizable end of the data stream transmission.”

At the institution phase, the Board accepted Amazon's contention that the primary reference, Feinberg, discloses “sessions,” but was later convinced by ZitoVault's expert testimony that “session” must refer to a connection with a defined beginning and end so that the server can determine which incoming data belongs to which session. At oral argument, Amazon conceded that a “session” would have a beginning and an end, but asserted that “there can't be any meaningful doubt” that Feinberg discloses a session with a recognizable beginning and end. In its final written decision, the Board narrowed its preliminary construction of “sessions” and held that Amazon failed “to identify what constitutes a 'session' in Feinberg.”

In her dissent, Judge Prost argued that the Board's analysis of the term, “sessions” was flawed, that Amazon never agreed that “sessions” must include protocol-level instructions for beginning and ending a data stream and the intrinsic evidence does not justify reading in this limitation.

- Summary (Paywall)

Fed. Cir. upholds narrow meaning of "defined"

In Impulse Technology Ltd. v. Microsoft et al., the Judge Lourie, writing for a two-judge panel with Judge Newman, agreed with Microsoft and the lower court that the a claim limitation reading “a tracking system for continuously tracking an overall physical location of a player in a defined physical space” should be narrowly construed. The claim is asserted against Microsoft's XBox “Kinect” 3D tracking system and game developers using Kinect. The lower court construed “defined physical space” to mean an “indoor or outdoor space having size and/or boundaries known prior to the adaption of the testing and training system.” The Federal Circuit agreed with Microsoft that this construction means prior to game play and specifically that the “defined physical space” must “be (1) known prior to adaption of the system, and (2) defined independently of the sensor viewing area.”

PTAB upholds rejection of unpatentability of claim with conditional language (posted 10/28/16)

In Ex Parte Schulhauser the PTAB found that a claim having conditional language “If X and If NOT X” was unpatentable when art only shows the “If X” part of the claim. The opinion focused on claim 1, reproduced to the right.

1. A method for monitoring of cardiac conditions incorporating an implantable medical device in a subject, the method comprising the steps of:

collecting physiological data associated with the subject from the implantable device at preset time intervals, wherein the collected data includes real-time electrocardiac signal data, heart sound data, activity level data and tissue perfusion data;

comparing the electrocardiac signal data with a threshold electrocardiac criteria for indicating a strong likelihood of a cardiac event; triggering an alarm state if the electro cardiac signal data is not within the threshold electrocardiac criteria;

determining the current activity level of the subject from the activity level data if the electrocardiac signal data is within the threshold electrocardiac criteria;

determining whether the current activity level is below a threshold activity level;

comparing the tissue perfusion data with a threshold tissue perfusion criteria for indicating a strong likelihood of a cardiac event if the current activity level is determined to be below a threshold activity level;

triggering an alarm state if the threshold tissue perfusion data is not within the threshold tissue perfusion criteria;

and triggering an alarm state if the threshold tissue perfusion data is within the threshold tissue perfusion criteria and the heart sound data indicates that S3 and S4 heart sounds are detected, wherein if an alarm state is not triggered, the physiological data associated with the subject is collected at the expiration of the preset time interval.

Appellants argued that the references failed to show “comparing the tissue perfusion data with a threshold tissue perfusion criteria for indicating a strong likelihood of a cardiac event if the current activity level is determined to be below a threshold activity level” or as recited in claim 1, reproduced to the right. The PTAB concluded that this step is not required of the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim. Specifically, the PTAB reasoned:

”[d]ue to the language in the “triggering” and “determining” steps, logically, the “triggering” and “determining” steps do not need to be performed, after the “comparing” step if the condition precedent recited in each step is not met. More specifically, the “triggering” and “determining” steps of this claim are mutually exclusive. If the electrocardiac signal data is not withint the threshold electrocardiac criteria,k kthen an alarm is triggered and the remaining method steps need not be performed. . . .

Based on the claim limitations as written, the broadest reasonable interpretation of claim 1 encompasses an instance in which the method ends when the alarm is triggered in response to the cardiac signal data not being within the electrocardiac criteria, such that the step of “determining the current activity level of the subject” and the remaining steps need not be reached. In other words, claim 1 as written covers at least two methods, one in which the prerequisite condition for the triggering step is met and one in which the prerequisite condition for the determining step is met. [. . .]

The Examiner in this case was able to present a prima facie case of obviousness as to claim 1 by providing evidence to show obviousness of the “collecting,” “comparing,” and “triggering” steps. The Examiner did not need to present evidence of the obviousness of doing the remaining method steps of claim 1 that are not required to be performed under a broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim. . . .

Fed. Cir. reverses PTAB invalidity finding (posted 04/07/16)

In Cutsforth v. MotivePower, the Fed. Cir. reversed PTAB's invalidity finding, looking specifically at two limitations that the BPAI construed unreasonably broadly in its determination that the claims were anticipated by two separate references.

In Cutsforth v. MotivePower, the Fed. Cir. reversed PTAB's invalidity finding, looking specifically at two limitations that the BPAI construed unreasonably broadly in its determination that the claims were anticipated by two separate references.

"projection"

The Fed. Cir. first addressed the claim limitation, “a brush release extending from the mounting block . . . said brush release is a projection extending from the mounting block.” The Board rejected Cutsforth's proposed construction “a structure that protrudes outwardly from the mounting block” as not supported by the specification and contended that the phrase is not limited only to projections extending outwardly from the mounting block. The Federal Circuit held that, while claims are given their broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) in IPR proceedings, claim interpretation “must be reasonable in light of the claims and specification” (quoting PPC Broadband Inc. v. Corning Optical Commc'ns RF, LLC (Fed. Cir. Feb. 22, 2016). Held the court: “The Board's interpretation of 'a projection extending from the mounting block' far exceeds the scope of its plain meaning and is not justified by the specification. We hold that the Board's interpretation, which encompasses a structure that recedes into themounting block rather than jutting out from it, is unreasonable.”

"coupled to"

The Federal Circuit also addressed a second limitation reciting, “a brush catch coupled to the beam.” The BPAI held despite this limitation, the “brush catch” may be a sub-component of the “beam” and still be considered to be “coupled to the beam.” The Federal Circuit again sided with Cutsforth's argument that the claim requires a “bursh catch” to be a physical structure that is separate from, and not a sub-component of, the claimed, “beam.” It goes beyond the plain meaning of “coupled” to say that a sub-component (e.g., an engine in a car) is “coupled to” the component as a whole (e.g., the car).

Federal Circuit refines Teva; intrinsic evidence subject to de novo legal analysis (posted 06/19/15)

The Federal Circuit, taking this case on remand from the Supreme Court (see below), in an opinion authored by J. Moore and joined by J. Wallach, again found Teva's patent claims to “molecular weight” invalid as indefinite. Specifically, the court held:

“A party cannot transform into a factual matter the internal coherence and context assessment of the patent simply by having an expert offer an opinion on it. The internal coherence and context assessment of the patent, and whether it conveys claim meaning with reasonable certainty, are questions of law. The meaning one of skill in the art would attribute to the term molecular weight in light of its use in the claims, the disclosure in the specification, and the discussion of this term in the prosecution history is a question of law. The district should not defer to Dr. Grant's ultimate conclusion about claim meaning in the context of this patent nor do we defer to the district court on this legal question. [. . .] Determining the meaning or significance to ascribe to the legal writings which constitute the intrinsic record is legal analysis. The Supreme Court made clear that the factual components include 'the background science or the meaning of a term in the relevant art during the relevant time period.' Teva cannot transform legal analysis about the meaning or significance of the intrinsic evidence into a factual question simply by having an expert testify on it. Determining the significance of disclosures in the specification or prosecution history is also part of the legal analysis. Understandings that lie outside the patent documents about the meaning of terms to one of skill in the art or the science or the state of the knowledge of one of skill in the art are factual issues. Even accepting as correct the district court's factual determinations about SEC and the transfer of chromatogram data to create Figure 1, these facts do not resolve the ambiguity in the Group 1 claim about the intended molecular weight measure.”

Judge Meyer dissented, arguing that key factual findings made by the district court were not clearly erroneous and therefore should be given deference. These findings were “(1) a person of ordinary skill in the art of polypeptide synthesis would infer from the use of the SEC method disclosed in the specification of the '808 patent that the term 'molecular weight' referred to peak average molecular weight; (2) a skilled artisan would not rely upon a statement Teva made when prosecuting the '847 patent that the expression of molecular weight in kilodalton units 'implie[d] a weight average molecular weight,' because that statement rested on obvious scientific error; and (3) that artisan would instead rely on Teva's affirmative statement, made while prosecuting the '539 patent, that 'molecular weight' meant peak average molecular weight.

Supreme Court reverses Circuit's rule for de novo claim construction (posted 01/20/15)

In Teva Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., the Supreme Court held that, when reviewing a district court's resolution of subsidiary factual matters made in the course of its construction of a patent claim, the Federal Circuit must apply a “clear error,” not a de novo, standard of review. Justice Breyer delivered the opinion of the Court.

The case comes to the Supreme Court on appeal by patent holder Teva from a Federal Circuit decision to invalidate a claim due to indefiniteness. Specifically, the Federal Circuit reversed a lower court ruling that the claim term, “molecular weight” referred to “peak average molecular weight” because that is what a skilled artisan would have understood at the time of the patent application. The Federal Circuit reached its invalidity determination based on de novo review of all aspects of the district court's claim construction, including subsidiary facts, in contravention of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)(6) which states that a court of appeals “must not . . . set aside” a district court's ”[f]indings of fact“ unless they are “clearly erroneous.”

The case comes to the Supreme Court on appeal by patent holder Teva from a Federal Circuit decision to invalidate a claim due to indefiniteness. Specifically, the Federal Circuit reversed a lower court ruling that the claim term, “molecular weight” referred to “peak average molecular weight” because that is what a skilled artisan would have understood at the time of the patent application. The Federal Circuit reached its invalidity determination based on de novo review of all aspects of the district court's claim construction, including subsidiary facts, in contravention of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)(6) which states that a court of appeals “must not . . . set aside” a district court's ”[f]indings of fact“ unless they are “clearly erroneous.”

The Supreme Court held that:

“In some cases . . . the district court will need to look beyond the patent's intrinsic evidence and to consult extrinsic evidence in order to understand, for example, the background science or the meaning of a term in the relevant art during the relevant time period. In cases where those subsidiary facts are in dispute, courts will need to make subsidiary factual findings about that extrinsic evidence. These are the “evidentiary underpinnings” of claim construction that we discussed in Markman, and this subsidiary factfinding must be reviewed for clear error on appeal”

Justice Thomas, joined by Alito, dissented, arguing:

“Patents are written instruments, so other written instruments supply the logical analogy. [. . .] The classic case of a written instrument whose construction does not involve subsidiary findings of fact is a statute. [. . .] The construction of deeds, by contrast, sometimes involves subsidiary findings of fact. [. . .] The question we must ask, then, is whether the subsidiary findings underlying claim construction more closely resemble the subsidiary findings underlying the construction of statutes or those underlying the construction of contracts and deeds that are treated as findings of fact. [. . .] This, in turn, depends on whether patent claims are more like statutes or more like contracts and deeds. [. . .] For purposes of construction, contracts and deeds are less natural analogies for patents. [. . .] In granting a patent, the Government is acting not as a party to a bilateral contract binding upon itself alone, but instead as a sovereign bestowing upon the inventor a right to exclude the public at large from the invention marked out by his claims. [. . .]

“Because the skilled artisan inquiry in claim construction more closely resembles determinations categorized as 'conclusions of law' than determinations categorized as 'findings of fact,' I would hold that it falls outside the scope of Rule 52(a)(6) and is subject to de novo review.”

- Oral Arguments: mp3 | transcript pdf | Stream:

CAFC clarifies "abstract"

In Ultramercial v. Hulu, the Fed. Cir. reviewed and reversed a dismissal by the district court of a patent because the claim was not patent-eligible subject matter. Chief Judge Rader reviewed the history of non-statutory subject starting with the Bilski decision, and held the following:

- The Supreme Court . . . recognized the difficulty of providing a precise formula or definition for the judge-made ineligible category of abstractness.

- Although abstract principles are not eligible for patent protection, an application of an abstract idea may well be deserving. . .” (citing Diehr, 450 U.S. at 187). - The application of an abstract idea to a “new and useful end” is the type of invention that the Supreme Court has described as deserving of patent protection, citing Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 67 (1972).

- Far from abstract, advances in computer technology–both hardware and software–drive innovation in every area of scientific and technical endeavor.

- Programming creates a new machine, because a general purpose computer once it is programmed to perform particular functions pursuant to instructions from program software, citing In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526, 1545.

- A broadly claimed method . . . [that] does not not specify a particular mechanism for delivering media content . . . does not render the claimed subject matter impermissibly abstract. Assuming the patent provides sufficient disclosure to enable a person of ordinary skill in the art to practice the invention and to satisfy the written description requirement, the disclosure need not detail the particular instrumentalities for each step in the process.

~UPDATED~ The Federal Circuit took a second look at this case on a second appeal from the district court, but this time after the Supreme Court's Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International case. On this appeal, the Federal Circuit held the patent to be invalid for failing to claim statutory subject matter.

Virtual is analogous to Physical (03/28/11)

In Innovation Toys v. MGA Entertainment (cached - 2up) the Fed. Cir. reversed the district court ruling that a virtual laser-based chess game was not analogous to the patented physical laser-based chess game. The case was then remanded to the District Court for reconsideration of its finding that the patent was non-obvious. The court relied on “Analogous Art” stalwarts In re Clay 2) and In re Bigio 3) in its holding that the prior art virtual game and the patented physical game are directed to the same purpose and address the same problem and are therefore analogous under Bigio.

Claim scope narrowed by spec; consideration of function OK (03/16/09)

In ICU Medical v. Alaris Medical Systems, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the district court's narrow construction of the term, “spike” as being “an elongated structure having a pointed tip for piercing the seal, which tip may be sharp or slightly rounded” stating that “it is 'entirely proper to consider the functions of an invention in seeking to determine the meaning of particular claim language.'” 4)

Cross posted: Valdidity-112

District Court: "providing a communications link" narrowly construed (02/27/09)

In Netcraft v. Ebay and Paypal (December 2007), the Western District of Wisconsin narrowly construed the phrase, “providing a communications link through equipment of the third party” as requiring, for infringement, that Defendants perform a step of providing Internet access to customers. The term, “communications link” was interpreted consistently with the specification as essentially Internet access. Since Ebay and Paypal are not Internet Service Providers, they did not perform this step, and therefore were not infringing. I am posting this because although it is a district court decision, it illustrates a common pitfall with the use of the word “providing” in method claims.

Fed. Cir. reverses BPAI anticipation rejection (12/22/08)

In In re Wheeler, a nonprecedential ruling, the CAFC reversed a rejection under 35 U.S.C. § 102 because the prior art fishing pole was not transparent along its entire length as claimed, having illumination only at its handle and tip. The PTO appears to have used faulty logic, arguing that despite what the claim read, the Wheeler pole is not transparent along its entire length. As the Fed. Cir. points out, “However, the ground of rejection is “anticipation,” and it is clear that Kelly does not show the Wheeler pole.”

Fed. Cir. affirms narrow construction of "partially" (06/15/08)

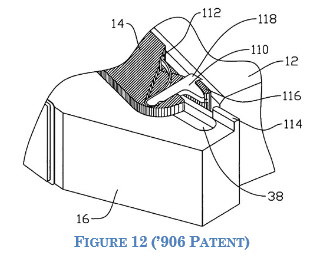

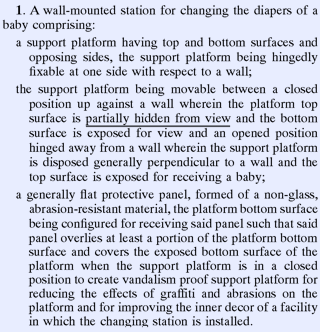

|

In Helmsderfer and Brocar Products, Inc. v. Bobrick Washroom Equip. Inc. et al., the Fed. Cir. upheld the Southern District of Ohio's ruling that “partially hidden” should be narrowly construed, i.e., as excluding “totally hidden.” Stated the court: “It is true that the plain meaning of 'partially hidden from view' does not include totally hidden from view, and that therefore claims 6-7 [which depend from claim 1 at right] do not cover the preferred embodiment or the other illustrated embodiments.” The fact that this construction “excludes both the preferred embodiment and every illustrated embodiment from these particular claims” is addressed by distinguishing Primos Inc. v. Hunter’s Specialties Inc. 5), which “counsels against interpreting a claim term in a way that excludes the preferred embodiment from the scope of the invention.” Primos and related cases are distinguished primarily on the basis that they prohibit “interpreting a claim term in a way that excludes disclosed embodiments, when that term has multiple ordinary meanings consistent with the intrinsic record” (emphasis added). Here, however, “Brocar’s proposed construction is not consistent with any plain meaning of the term “partially” as interpreted in light of the specification.”

"As" should be read in its context (01/19/08)

In Innogenics v. Abbott Laboratories, the Federal Circuit was highly critical of Abbott's lawyers, and ruled against Abbott on a variety of procedural grounds. With respect to claim construction matters, the Fed. Cir. sided with the district court in rejecting Abbott's proposed construction of the word “as” in the limitation, “detecting a complex as formed with said probe and said nucleic acids of HCV.” Abbott argued “that the word 'as' limits the claims at issue to detecting hybridized complexes in a contemporaneous manner.” Stated the court, “Abbott’s proposed construction unduly limits the claims of the ’704 patent by divorcing the word 'as' from its full context, 'as formed with said probe and said nucleic acids of HCV,'” citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 6).

Fed. Cir. defines "user"; applies 102(g) (11/29/07)

In z4 Techs., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 7) the Fed. Cir. reversed the lower court ruling and agreed with Microsoft that the term “user” cannot read on “computer” or “computers” because such a construction “conflicts with 'both the plain language of the claims and the teachings of the specification,' NeoMagic Corp. v. Trident Microsystems, Inc., 8).” As examples, the court pointed to limitations reading “enabling the software on a computer for use by a user,” and “comparing previously stored registration information . . . to at least one of the software, the user, and the computer.” Although the court agreed that the term, “user” is limited to a person or a person using a computer, the court disagreed with Microsoft that it changes the lower court's claim construction since “both the claims and specification describe methods of [determining whether a user is authorized] based on computer-specific information, among other things.” Therefore, although a user is a person, he can be identified on the basis of computer-specific information, which is how the district court identified “user” in the first place.

The Fed. Cir. further affirmed, with somewhat muddled logic, the lower court's construction of “requiring” in relation to “password” or “authorization code” limitations in the face of Microsoft's arguments. Microsoft argues that since any product key supplied by Microsoft's accused products can be used with any copy of the software, they avoid the asserted claims, which read, “associating a first authorization code with the software, the first authorization code enabling the software . . . for an initial authorization period, . . . supplying the first authorization code with the software; [and] requiring the user to enter the first authorization code to [activate the grace period].” In reaching its conclusion, the Fed. Cir. pointed to evidence establishing that “in the ordinary course of activating a copy of the accused software, a user is required to enter an authorization code—the Product Key—associated with that copy of the software.” The court concluded, ”[e]ven if the potential use of unassociated Product Keys to enable software grace periods may be framed as a 'non-infringing mode[] of operation,' our conclusion remains the same.“

With respect to “automatic” or “electronically” limitations, the Fed. Cir. dismisses Microsoft's arguments as “without merit.” Specifically, Microsoft suggested that the claims require that, “once users choose the electronic or automatic registration mode (as contrasted with the manual mode), the initiation of the registration communication must commence without any user interaction.” The court noted, however, that the claims are silent with respect to the initiation of the registration process.

- See prior_use for the court's holdings on application of 35 U.S.C. §102(g).

Claim reads on indirect measurement, indirectly (09/09/07)

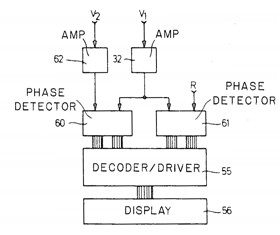

In Mitutoyo Corp. et al. v. Central Purchasing, Central Purchasing appeals the district court ruling that Central Purchasing infringed U.S. Patent 4,743,902 in contravention of a 1994 settlement agreement between the parties. The Fed. Cir. rejected Central Purchasing's argument that claim 1 is not literally infringed because, in the accused device, the phase angle is measured between a received signal and a reference signal, and not between the received signal and the supply signal signal, as described in the '902 patent. Stated the court: “Neither the stipulated claim construction nor the language of claim 1 require calculation of the phase angle by direct comparison of the supply signal and the received signal. Instead, they merely require the phase angle to be calculated based on some comparison of those two signals, even an indirect one.” (Read more on this case on issues of damages, willfulness, and standing.)

In Mitutoyo Corp. et al. v. Central Purchasing, Central Purchasing appeals the district court ruling that Central Purchasing infringed U.S. Patent 4,743,902 in contravention of a 1994 settlement agreement between the parties. The Fed. Cir. rejected Central Purchasing's argument that claim 1 is not literally infringed because, in the accused device, the phase angle is measured between a received signal and a reference signal, and not between the received signal and the supply signal signal, as described in the '902 patent. Stated the court: “Neither the stipulated claim construction nor the language of claim 1 require calculation of the phase angle by direct comparison of the supply signal and the received signal. Instead, they merely require the phase angle to be calculated based on some comparison of those two signals, even an indirect one.” (Read more on this case on issues of damages, willfulness, and standing.)

Fed. Cir. limits "coupled" to disclosed embodiment (08/10/07)

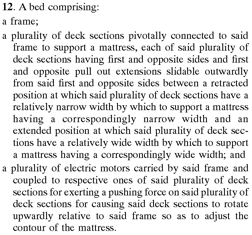

In SafeTCare Manufacturing, Inc. v. Tele-Made, Inc. et al. (Cached) the Fed Cir. was faced with a claim construction issue wherein claim 12 required “a plurality of electric motors . . . coupled to respective ones of said plurlaity of deck sections for exerting a pushing force on said plurality of deck sections. . . .” The Fed. Cir. held that “Claim 12 does not require that the motor exert a force directly on the deck section because Claim 12 contemplates intermediates between them.” However, the Fed. Cir. narrowed its construction on the basis of the disclosure, concluding that “the specification precludes SafeTCare’s broad interpretation.” Specifically, the court held that “despite the fact that Claim 12 makes no mention of actuators or lift dogs, the patentee repeatedly emphasized its invention as applying pushing forces as opposed to pulling forces against the lift dogs” and that this mechanism is superior to prior art actuators that pull against the lift dogs. Stated the court: We 'recognize that the distinction between using the specification to interpret the meaning of a claim and importing limitations from the specification into the claim can be a difficult one to apply in practice.' In this case, however, . . . we are persuaded by the language used by the patentee that the invention disclaims motors that use pulling forces against lift dogs.”

In SafeTCare Manufacturing, Inc. v. Tele-Made, Inc. et al. (Cached) the Fed Cir. was faced with a claim construction issue wherein claim 12 required “a plurality of electric motors . . . coupled to respective ones of said plurlaity of deck sections for exerting a pushing force on said plurality of deck sections. . . .” The Fed. Cir. held that “Claim 12 does not require that the motor exert a force directly on the deck section because Claim 12 contemplates intermediates between them.” However, the Fed. Cir. narrowed its construction on the basis of the disclosure, concluding that “the specification precludes SafeTCare’s broad interpretation.” Specifically, the court held that “despite the fact that Claim 12 makes no mention of actuators or lift dogs, the patentee repeatedly emphasized its invention as applying pushing forces as opposed to pulling forces against the lift dogs” and that this mechanism is superior to prior art actuators that pull against the lift dogs. Stated the court: We 'recognize that the distinction between using the specification to interpret the meaning of a claim and importing limitations from the specification into the claim can be a difficult one to apply in practice.' In this case, however, . . . we are persuaded by the language used by the patentee that the invention disclaims motors that use pulling forces against lift dogs.”

Fed. Cir. splits on infringement and validity in cord blood case (07/18/07)

In PharmaStem Therapeutics, Inc. v. Viacell, Inc., et al., the Fed. Cir. affirmed the district court's finding of infringement and overruled the non-obviousness. With respect to infringement, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the lower courts JMOL (which overruled the jury) stating that PharmaStem failed to prove infringement of “an amount [of cord blood] sufficient to effect reconstitution [of blood stem cells in] a human adult” since it did not use direct testing or other scientific evidence to prove that any particular cord blood sample or group of samples preserved by any of the defendants contained enough stem cells to reconstitute progenitor cells in a human adult. Reliance on defendants' admissions “various statements by each of the defendants that the cord blood samples they preserved could be potentially useful not only for the donor but also for the donor’s relatives, including adult relatives” was misplaced. Stated the court: “none of the statements represented that the stem cells in any of the cryopreserved cord blood samples were sufficient in number to effect hematopoietic reconstitution of an adult, as is required by claim 1 of the reexamined ’681 patent. Instead, the defendants’ statements emphasized the potential therapeutic usefulness of the cord blood in general and referred to future uses of stored blood in adult transplants only as possibilities.”

In her inevitable dissent, Judge Newman notes, “The defendants' testimony was uniformly to the effect that this “possibility” was the purpose of their preservation service (the record also describes a case in which the cord blood was used to treat the mother's existing disease). The evidence was that most but not all of the cryopreserved cord blood that has been transplanted was to children, with about ten percent transplanted to adults. PharmaStem is correct that this ratio relates to damages, and does not simply serve to negate all liability for infringement.”

Fed. Cir. reverses on claim scope in broadened continuation (07/02/07)

In Saunders Group v. Comfortrac (Fed. Cir. 2007), the Fed. Cir. reversed the lower court's claim construction, which held that the limitation to “pneumatic cylinder” necessarily included a “pressure activate seal” as that was the only embodiment disclosed in the application, and the written description suggested that the pressure activated seal was necessary to maintain pneumatic pressure. In reversing the district court, the Fed. Cir. emphasized the doctrine of claim differentiation as requiring the broader interpretation of the broader claims. Furthermore, the Fed. Cir. noted that a petition to make special “asserted . . . that a device lacking a pressure activated seal infringed . . . only those claims that lacked a pressure activated seal requirement and that the accused device had no pressure activated seals.” The Fed. Cir. declined to decide any issues of infringement, and remanded to the district court for futher proceedings, leaving the possibility of invalidating the claims for failing to enable the full scope thereof.

Fed. Cirl holds "near" is definite; information submitted in Reexam "cures" previous omission (07/01/07)

In Young v. Lumenis, Inc., the Fed. Cir. reversed the district court's ruling that Young's claim, directed to a surgical technique for declawing domestic cats, “is invalid for indefiniteness because . . . it would be impossible for someone skilled in the art to determine the meaning of ‘near’ so as to avoid infringement.” In reaching its conclusion, the district court relied on Amgen, Inc. v. Chugai Pharm. Co., Ltd. 9), for the principle that a word of degree can be indefinite when it fails to distinguish the invention over the prior art and does not permit one of ordinary skill to know what activity constitutes infringement. However the Fed. Cir. distinguishes Amgen, stating that the record in that case did not contain sufficient intrinsic evidence to make a reasonable determination of “at least about 160,000 IU per absorbance unit” to determine whether the prior art was within the range or not, particularly when coupled with an expected measurement error. In contrast, the intrinsic evidence adequately identifies the scope of “near” which is particularly justifiable since the term “near” is in reference to a location in biology, which varies from one animal to another.

The Fed. Cir. also reversed the district court's finding of inequitable conduct. Here, the district court relied on Rohm & Haas Co v. Crystal Chemical Co. 10) stating that, since Young failed to cure the inequitable conduct on their own initiative, their submission following Lumenis's motion for summary judgement was not sufficient to cure the inequitable conduct. The Fed. Cir., however, distinguished the facts in Rohm & Haas, stating that in that case, the inequitable conduct was an alleged false affidavit, “where a cure hurdle may be higher than here” which involves an alleged omission.

Fed. Cir. affirms construction of "slidably engage" (05/04/07)

In a very straight-forward opinion in Foremost in Packaging Systems, Inc., v. Cold Chain Technologies, Inc., the Fed. Cir. affirmed the lower court's ruling that Cold Chain's product (Fig. B below) does not meet the claim limitation of “the insulated block being adapted to slidably engage the coolant cavity, thereby the coolant and the insulated block together substantially filling the coolant cavity” because the insulated block and the coolant do not “together” substantially fill the coolant cavity. Citing Cf. Depuy Spine, Inc. v. Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc. 11), the court further agreed that Foremost cannot establish infringement by invoking the DoE in the present circumstance.

In addition, the Fed. Cir. agreed with the district court's interpretation of the functional limitation of claim 22:, “an insulated cover adapted to engage the open end of the insulated body and having a configuration for minimizing air spaces within the cavities.” The court reasoned that “the only way the insulated cover can have 'a configuration for minimizing air spaces within the cavities' is if the cover is designed so that part of it extends downward into and therefore fills part of the cavity.”

Reversal on "intermediary" (04/28/07)

In Intamin v. Magnetar Technologies, the Fed. Cir. reversed the lower court's holding that a claim to “intermediaries” between magnets of alternating polarity used in a roller-coaster braking apparatus is limited to non-magnetic intermediaries. The district court reasoned that Magnatar did not infringe because their device has a series of magnets having 90° rotations and therefore lacks non-magnetic intermediaries. The Fed. Cir., however stated that the claim language itself does not require a non-magnetic intermediary, that a narrow disclosure in the specification does not necessarily limit broader claim language, and in the present case, the “overall context of the patent” does not “specifically disavow magnetic intermediaries.” The opinion touches on the doctrine of claim differentiation, arguing that claim 2, which states “wherein said intermediary is non-magnetic” buttresses the broader interpretation of claim 1, but that claim 1 should have been broadly interpreted by the district court even without looking to claim differentiation. The Fed. Cir. accordingly vacated the district court's claim construction and remanded for further consideration on infringement.

In a cross-appeal, Magnetar argued that the district court abused its discretion in denying Rule 11 sanctions against Intamin. Specifically, Magnetar argues that Intamin did not conduct a good faith investigation of Magnetar's product before filing its complaint because they did not obtain and cut open the metal casing on the magnets to determine whether the device infringed the claims. The Fed. Cir. found that, in denying Magnatar's motion, the district court did not abuse its discretion since Intamin analyzed the patent's validity, determined the scoep of the claims and performed infringement analysis based on publicly available documents on Magnetar's brakes, inspected and photographed the brakes and reviewed them with experts.

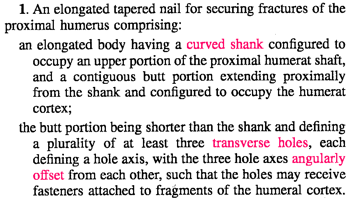

Fed. Cir. splits on "transverse" (04/19/07)

In Acumed v. Stryker, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the lower court's ruling of willful infringement, but vacated and remanded on the issuance by the lower court of an injunction. Judge Anna Brown wrote the majority opinion, which held that “transverse” does not mean “perpendicular” despite the fact that the only embodiment described in the specification contains through-holes that are all perpendicular to the butt portion of the shank. Stryker literally infringed despite the fact that the through-holes in Stryker's device are not perpendicular to the butt portion of the shank. Judge Kimberly Moore dissented, stating that based on her reading of the specification, “transverse” is defined as “perpendicular,” and therefore not literally infringed. She did strongly hint, however, that the claims may be infringed under the doctrine of equivalence.

In Acumed v. Stryker, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the lower court's ruling of willful infringement, but vacated and remanded on the issuance by the lower court of an injunction. Judge Anna Brown wrote the majority opinion, which held that “transverse” does not mean “perpendicular” despite the fact that the only embodiment described in the specification contains through-holes that are all perpendicular to the butt portion of the shank. Stryker literally infringed despite the fact that the through-holes in Stryker's device are not perpendicular to the butt portion of the shank. Judge Kimberly Moore dissented, stating that based on her reading of the specification, “transverse” is defined as “perpendicular,” and therefore not literally infringed. She did strongly hint, however, that the claims may be infringed under the doctrine of equivalence.

- Summary

Another estoppel case (04/14/07)

Judge Newman authored the opinion in Bass Pro Trademarks L.L.C. v. Cabela's, Inc. reversing the trial court which held the term “vest” does not require a full front and back garment since the term appears only in the preamble of the claim, and the backpack/seat product sold by Cabela's Inc. literally infringed the remaining claim elements. Bass Pro inserted the term “vest” during prosecution and distinguished the invention from a prior art backpack frame capable of being converted into a chair by stating the prior art device has “no vest or other type garment to which it attaches.” Because of this and other statements (see full opinion) Judge Newman, citing the prosecution history and Phillips v. AWH Corp., concluded, ”[i]t is clear that this patentee procured the patent based on the “unique combination of vest and pivotable seat member” and vacated the lower court's ruling.

Fed. Cir. Warns Applicants to rescind disclaimers when filing continuations (02/23/07)

In Hakim v. Cannon Avent Group, PLC, et al., the Fed. Cir. states “Hakim had the right to refile the application and attempt to broaden the claims. […] However, an applicant cannot recapture claim scope that was surrendered or disclaimed. The district court did not err in holding that the examiner's action in allowing the continuation claims without further prosecution was based on the prosecution argument in the parent. […] Although a disclaimer made during prosecution can be rescinded, permitting recapture of the disclaimed scope, the prosecution history must be sufficiently clear to inform the examiner that the previous disclaimer, and the prior art that it was made to avoid, may need to be re-visited” (emphasis added).

Fed Cir. melts Dippin' Dots (02/13/07)

In Dippin' Dots, Inc., et al. v. Mosey, et al. v. Esty, Jr., et al., the Fed. Cir. held that Dippin' Dots is estopped from arguing the term “bead” could include popcorn shaped pieces formed by multiple spherical shapes that are stuck together when previously Dippin' Dots argued that a bead is spherical. In addition, the Fed. Cir. agreed with the circuit court that a method claim having the phrase “comprising the steps of” does not open the individual steps to additional features, but simply allows additional steps to be performed.

Fed. Cir. Reverses on "values associated with" (01/30/07)

In Time 'N Temperature v. Sensitech, the Fed. Cir. disagreed with Sensitech, who argued that a claim limitation reading “first storage means for storing values associated with selected portions of said signal” requires that the stored values reflect some type of mathematical computation. While this argument apparently worked at the district court, the Fed. Cir. reversed, finding that the phrase “values associated with” is used in a manner that encompasses the storage of simple readings. Furthermore, even with the more narrow definition argued by Sensitech, the prior art reference meets it.

Fed. Cir. Narrows Claims in light of Prosecution History (01/29/07)

In Anderson Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC, the Fed. Cir. found that the prosecution history estopped Anderson Corp. from arguing that the product claims did not include the method of making the products since Anderson argued during prosecution, “the presently claimed composite is prepared by mixing the melted polymer and wood pulp, forming pelletized material, cooled, then extruded. This affords a smooth structural member without any evidence of polyvinyl chloride degradation.”

Fed. Cir. broadens claim construction, reverses District Court of Mass (01/25/07)

In MBO Laboratories, Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson & Co., the Fed. Cir. touches on the claims terms, “proximate,” “mounted on,” “adjacent” and others, as well as the recapture rule. The Fed. Cir. significantly broadened the claim construction arrived at by the district court, and found infringement. The Fed. Cir. did not address the validity of the patent.

Fed.Cir. rules: "About 5" = 3.6 to 7.1 (01/22/07)

In Ortho-McNeil Pharm. v. Caraco Pharm., the Fed. Cir., upheld the lower-court's ruling that a ratio of 1:5 should be construed as a range from 1:3.6 to 7.1 based on expert testimony which was based on a confidence interval constructed from the data in the patent. The Doctrine of Equivalents was not extended to the claims because the patentee canceled broader “comprising” claims during the course of prosecution.

Fed. Cir. construes "secured" as detachable in light of disclosure (11/15/06)

In AKEVA L.L.C., v. ADIDAS-SALOMON AG,, the Fed. Cir. relied on language in the spec to interpret the claim term, “secured” as being releasable.

Medtronic loses on recapture argument (10/16/06)

During proseuction, Guidant amended some claims which were later broadened in a reissue application that was eventually granted. Medtronic claimed that, in the reissue, Guidant improperly recaptured subject matter which was surrendered during prosecution. The Fed. Cir. disagreed in Medtronic, Inc. v. Guidant Corporation, et al., a non-precedential opinion.

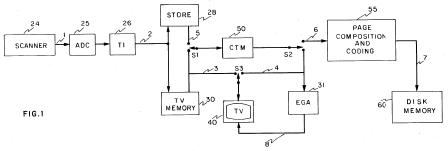

Making Copies: ''MIT v. Abacus'' (09/13/06)

In MIT v. Abacus Software Fed. Cir., Sept. 2006, MIT argued that its patent for a “scanner” included a digital camera and that “colorant selection mechanism” does not fall under §112 ¶6. MIT loses. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the scanner must have “relative movement between the scanning element and the object being scanned.” With regard to the §112 issue, the Federal Circuit noted that “The generic terms 'mechanism,' 'means,' 'element,' and 'device,' typically do not connote sufficiently definite structure.” The court, however, also found that the phrase “aesthetic correction circuitry” has “enough substance to elude the straightjacket of mean-plus-function construction.” Go figure. :)

In MIT v. Abacus Software Fed. Cir., Sept. 2006, MIT argued that its patent for a “scanner” included a digital camera and that “colorant selection mechanism” does not fall under §112 ¶6. MIT loses. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the scanner must have “relative movement between the scanning element and the object being scanned.” With regard to the §112 issue, the Federal Circuit noted that “The generic terms 'mechanism,' 'means,' 'element,' and 'device,' typically do not connote sufficiently definite structure.” The court, however, also found that the phrase “aesthetic correction circuitry” has “enough substance to elude the straightjacket of mean-plus-function construction.” Go figure. :)

Fed. Cir. interprets "Consists Of" (08/17/06)

In Conoco Inc. v. Energy Environmental Internat'l, the Fed. Cir. found “consisting of” to not exclude impurities.

Fed. Cir.: "This Invention" Limits Claim Scope (06/26/06)

Honeywell v. ITT Industries (Fed. Cir. 2006). On appeal of a summary judgment of noninfringement, the CAFC considered the meaning of the claim term “fuel injection system component.” On four occasions, the specification refers to to “this invention” as relating to a “fuel filter.” And, the specification does not indicate that a fuel filter is merely a preferred embodiment. Consequently, the CAFC concluded that the patentee limited the scope of the patent claims to require a fuel filter.

Precedential Opinion: Steps for defining claim terms (April, 2004)

In an en banc deicision, the Fed. Cir. in Edward H. Phillips v. AWH Corp. (html) 12) (erratum), found that intrinsic evidence, the context, the specification, and prosecution history, should be first looked to for the definition of claim terms, then extrinsic evidence such as dictionary definitions.

In an en banc deicision, the Fed. Cir. in Edward H. Phillips v. AWH Corp. (html) 12) (erratum), found that intrinsic evidence, the context, the specification, and prosecution history, should be first looked to for the definition of claim terms, then extrinsic evidence such as dictionary definitions.

- Brief review, link to MP3 of decision