Navigation

Table of Contents

Doctrine of Equivalents

The doctrine of equivalents allows a court to hold a party liable for patent infringement even though the infringing device or process does not fall within the literal scope of a patent claim, but nevertheless is equivalent to the claimed invention.

Fed. Cir.: Doctrine of Equivalents is not a line-drawing exercise (posted 12/14/23)

Patent in suit:

U.S. Patent 7,725,759

In VLSI Technology LLC, v. Intel Corporation 1) the court outlined three limitations on the use of the Doctrine of Equivalents (DoE) in claim construction:

“First, proof of equivalents must be limitation specific, not focused only on the claim as a whole, though the limitation-specific inquiry . . . may be informed by the role played by each element in the context of the specific patent claim.”

“Second, for the determination of whether a substitute element is only insubstantially different from a claimed element and hence an equivalent, a traditional formulation . . . asks whether a substitute element matches the function, way, and result of the claimed element.”

“Third, . . . [t]he patentee must provide particularized testimony and linking argument as to the insubstantiality of the differences between the claimed invention and the accused device.”

Claim 14, in part:

a first master device . . . configured to provide a request to change a clock frequency of a high-speed clock in response to a predefined change in performance of the first master device, wherein the predefined change in performance is due to loading of the first master device as measured within a predefined time interval;

VSLI argued that Intel's “. . . Lake . . .” line of microprocessors infringe claim 14 of the '759 patent under the DoE. VLSI proposes that it is a combination of (1) “the core” and (2) “the core-specific p-code” residing on the power control unit that makes the frequency-change request.

VSLI's expert testified that the combination of components provides a request in substantially the same way as claimed because, “it's the first master device and its [p]-code that provides the request.”

The court found this testimony lacking because:

“[i]t contains no meaningful explanation of why the way in which the request is made is substantially the same as what the claim prescribes. The question is not whether, in a schematic drawing used to illustrate functions, an engineer could 'draw . . . [a] line” in different places. The question is about actual functionality-location differences. It is not enough . . . to say that the different functionality-location placements were a 'design choice.' [. . .] The question that must be addressed is whether the difference in the way the functionalities are actually allocated between devices is an insubstantial one.“

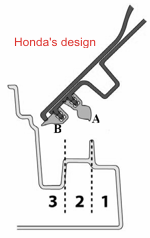

File wrapper estoppel nixes doctrine of equivalents (04/16/09)

In Felix v. American Honda Co., the Federal Circuit affirmed a Summary Judgment finding patent 6,155,625 not literally infringed and estopped from a doctrine of equivalents when the applicant canceled broad claims and incorporated them into dependent claims. With respect to the literal infringement, the Fed. Cir. rejected four arguments put forth by Felix. The court was particularly testy due to misrepresentations by Felix as to how the dictionary defined the terms “mounted” and “engaging.” In both cases, the court rejected broad construction of these terms, electing to define “mounted” as “securely affixed or fastened to” and “engaging” as “forming a seal” but not “bring together” as argued for by Felix, or “latching” as the district court held.

With regard to the doctrine of equivalents, the court noted that Felix rewrote claim 7 , which included “a weathertight gasket mounted on said lip and engaging said lid in its closed position,” into independent form. Citing Festo, the Fed. Cir. held that, by adding these limitations into the broader canceled claim 1, Felix gave rise to a presumption of surrender. The fact that this first amendment did not succeed in obtaining an allowance and that a further amendment was required is of no consequence to the estoppel effect of the first amendment. Also, it was immaterial that the cancellation and amendment were to claims 1, 7, and 14, rather than to claims 8 and 16 which resulted in the asserted claim. Quoting Deering, “The presumption of surrender applies to all claims containing the [added] [l]imitation, regardless of whether the claim was, or was not, amended during prosecution.”2) Felix's arguments that the amendment was made for a different purpose and therefore only tangentially related to the gasket position was rejected. Stated the court, “If Felix had intended only to add a channel and not add a gasket, he could easily have simply amended original claim 1 to add limitation (e) and not limitation (f).

Festo Returns, defines "foreseeability" (07/14/07)

In the latest iteration of Festo Corp. v. SMC Corp., (Festo XIII), the Fed. Cir. finds that an equivalent is foreseeable when “it is disclosed in the pertinent prior art in the field of the invention. In other words, an alternative is foreseeable if it is known in the field of the invention as reflected in the claim scope before amendment.” Thus, the foreseeable equivalent is not required to satisfy the function/way/result test. In this case, aluminum, a non-magnetizable material, was well known in general and therefore foreseeable, but its utility to provide magnetic field shielding was unknown at the time of the amendment. Moreover, the prior art did not support forming the sleeve out of aluminum. However, since the use of aluminum was foreseeable, the Fed. Cir. found that Festo's claim amendment limiting the sleeve to a “magnetizable material” estopped them from claiming the aluminum sleeve as an equivalent. In another blistering dissent, J. Newman states, “this court has confounded the issue by creating a new and incorrect criterion for the measurement of 'foreseeability,' the court now holding that an existing structure need not be recognized, or even recognizable, as an equivalent at the time of the patent application or amendment, in order to be 'foreseeable' if it is later used as an equivalent.”

- Summary, analysis

Fed. Cir. affirms narrowness of tangentiality doctrine for narrowing amendments during prosecution in avoiding Festo under the DoE (03/25/07)

In Cross Medical v. Medtronic, the Fed. Cir. reversed the lower court's ruling that Cross Medical's patent was infringed by Medtronic's polyaxial screw, used in spinal immobilizers. Cross Medical narrowed the claims during prosecution to overcome a 35 USC §112 rejection, which invoked Festo, in that equivalents of the subject matter disavowed by the narrowing amendment were surrendered. Cross Medical argued that the purpose of the amendment was only tangentially related to the equivalents and that the equivalents disavowed were not foreseeable at the time the amendment was made. The Fed. Cir. disagreed with both arguments.

- More.

- Summary and Review

Fed. Cir. says Middle District of Tennessee is right, but for wrong reason on DoE (03/03/07)

In Aquatex Industries, Inc. v. Techniche Solutions, the Fed. Cir. held that the Middle District of Tennessee erred in issuing a summary judgment in favor of Techniche, the accused infringer. First, the district court erroneously held that infringement by the doctrine of equivalents is barred by prosecution history estoppel. Specifically, Aquatex amended their claim to read a “method of cooling a person by evaporation.” In addition, the district court erroneously concluded that the function of the “fiberfill batting material” was to promote evaporation and that Vizorb® did not achieve this function in the same way (i.e., by the use of hydrophobic material and by the creation of air pockets) as this limitation. The Fed. Cir. noted that the narrowing amendment bore no relation to the fiberfill batting material and the record does not support the district court's conclusions as to the function of the fiberfill batting material. However, the Fed. Cir. also found that evidence of equivalence proffered by Aquatex was insufficient to overcome a motion for summary judgment, and affirmed.

District court affirmed: D.O.E. infringement "not clearly erroneous" (11/15/06)

In Abraxis Bioscience, Inc. v. Mayne Pharma Inc., the Fed. Cir. upheld the lower court's finding of infringement under the D.O.E. Stated the court: “Unlike claim construction, a matter of law reviewed de novo, infringement under the doctrine of equivalents is a factual determination that we review for clear error. Centricut, LLC v. Esab Group, Inc., 390 F.3d 1361, 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2004). Thus, notwithstanding our disagreement with the district court's conclusions regarding claim construction and literal infringement, we will affirm its decision on infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.”