Navigation

Table of Contents

Means plus function limitations

Fed. Cir.: "Code"/"application" are not "nonce" terms (posted 05/18/22)

March 24, 2020: In Dyfan, LLC v. Target Corp., the Federal circuit reversed a Markman holding by W.D.Texas (J. Albright) that certain claim terms formulated as “said code, when executed, further configured to . . .” are subject to § 112 ¶ 6 interpretation, leaving the claims indefinite for lack of corresponding structure in the written description.

The Federal Circuit (Judges Laurie, Dyk, and Stoll) agreed with the District court's finding that, because the word “means” does not appear in the claim, there is a presumption against applying § 112 ¶ 6. However, the Fed. Cir. reversed the lower court's ruling that 112(6) applied. The Fed. Cir. based its reversal on expert testimony presented at trial that “code” and “application” convey structure and are not simply nonce terms. Stated the court:

“To overcome this presumption, Target had to show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that persons of ordinary skill in the art would not have understood the “code”/“application” limitations to connote structure in light of the claim as a whole. [. . .] But the district court erred by ignoring key evidence–unrebutted deposition testimony from Target's own expert, Dr. Goldberg–regarding how a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the “code”/“application” limitations. [. . .]

“Dr. Goldberg testified that here, 'application' is 'a term of art' that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood as a particular structure [and] would have been commonly understood to mean a 'computer program intended to provide some service to a user,” and that developers could have, at the relevant time, selected existing 'off-the-shelf software' to perform specific services and functions.

“Additionally, Dr. Goldberg testified that persons of ordinary skill would have understood that the word 'code,' when coupled with language describing its operation, here connotes structure. Dr. Goldberg explained that a person of ordinary skill would understand that 'code' is 'a bunch of software instructions' [and] that a person of ordinary skill would have known that the claimed function of displaying information could be implemented using 'off-the-shelf' code or applications.”

On the basis of this unrebutted testimony, the Federal Circuit panel concluded that “the claim limitations do not recite 'purely functional language' [but] instead . . . the 'code'/'application' limitations here connote a class of structures to a person of ordinary skill.”

En Banc Review

UPDATE: An amicus brief, submitted by Mark Lemley of Stanford Law and authored by over 20 IP law professors urged the court to grant rehearing en banc as requested by Target. The petition argued that the “panel opinion is inconsistent with this Court's en banc decision in Williamson v. Citrix. Stated the brief:

Prior to Williamson, software patentees frequently claimed to own the function of their program, not merely the particular way they achieved that goal. Both because of the nature of computer programming and because they avoided using the term “means” in favor of equally empty nonce words like “module” or “mechanism,” those patentees wrote those broad functional claims without being subject to the limitations of section 112(f). As a result, they effectively captured ownership of anything that achieves the goal the patent identifies. They claimed to own the function itself. And quite often they did so without ever having disclosed any way of achieving that goal, much less every way. That “resulted in a proliferation of functional claiming untethered to section 112, para. 6 and free of the strictures set forth in the statute.” Williamson, 792 F.3d at 1349.

Williamson put an end to that practice – until now. [. . .]

The panel opinion credited testimony that off-the-shelf software could perform the functions in question.2 But even assuming that is true, it has no bearing at all on whether the words “code” and “application” invoke section 112(f) in the first place. At most it goes to the question of whether the patent is indefinite, or whether the patentee can show that the patent sufficiently discloses structure in the form of an algorithm by pointing to that off-the-shelf software. But it does not mean that the terms “code” and “application” by themselves provide that structure. They don’t. They are merely generic references to the idea of using software to achieve a goal.

If software patentees can avoid Williamson and write purely functional claims merely by using the word “code” in place of actual structure, this Court will have rendered Williamson a dead letter.

The petition was denied without comment.

Fed. Cir. reverses 101 invalidity, addresses means+function definiteness on "self referential database" (posted 05/17/16)

On May 12, 2016, in Enfish v. Microsoft Corp., the Fed. Cir. reversed a district court ruling of invalidity under § 101 of a claim directed to a self referential database.

On May 12, 2016, in Enfish v. Microsoft Corp., the Fed. Cir. reversed a district court ruling of invalidity under § 101 of a claim directed to a self referential database.

§ 112 definiteness

The court rejected Microsoft's argument that the means-plus-function element in claim 17 is indefinite under 35 U.S.C. § 112, finding that the district court's 4-step algorithm sufficiently identified a structure for a person of skill in the art to implement the function of “configuring said memory according to a logical table.”

Stated the court:

- “The fact that this algorithm relies, in part, on techniques known to a person of skill in the art does not render the composite algorithm insufficient under § 112 ¶ 6. Indeed, this is entirely consistent with the fact that the sufficiency of the structure is viewed through the lens of a person of skill in the art and without need to 'disclose structures well known in the art,' 1).

⚠️ On patent eligibility, see this court's holdings at statutory_subject_matter

Federal Circuit asserts Williamson on all claim types (posted 09/08/15)

Claim 1. A method of preventing unauthorized recording of electronic media comprising:

activating a compliance mechanism in response to receiving media content by a client system, said compliance mechanism coupled to said client system, said client system having a media content presentation application operable thereon and coupled to said compliance mechanism;

controlling a data output path of said client system with said compliance mechanism by diverting a commonly used data pathway of said media player application to a controlled data pathway monitored by said compliance mechanism; and

directing said media content to a custom media device coupled to said compliance mechanism via said data output path, for selectively restricting output of said media content.

In Media Rights Technologies ("MTD"), Inc., v. Capital One Financial Corporation, et al., Judge O'Malley, writing for the Federal Circuit, affirmed the lower court's decision on Summary Judgment invalidating all claims of U.S. Patent 7,316,033, claim 1 of which is shown to the right. The subject patent includes claims of every category, including method, apparatus, and computer-readable-media.

Citing Williamson and Apex, the court stated that the “presumption against the application of § 112, ¶ 6 to a claim term lacking the word, 'means' can be overcome if a party can demonstrate that the claim term fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or else recites function without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function” (internal quotations removed). Media Rights, as the patent holder, argued that the specification included adequate structure to support the definiteness of “compliance mechanism.” However, the court held that not all four of the identified functions of “compliance mechanism” are supported by the specification. Specifically, the court held “the specification fails to disclose an operative algorithm for both the 'controlling data output' and 'managing output path' functions.” The court further held that the specification failed to disclose sufficient structure for the “monitoring” function.

Useful quote: “Generic terms like . . . ‘element’ . . . are commonly used as verbal constructs that operate, like ‘means,’ to claim a particular function rather than describe a ‘sufficiently definite structure.’” MTD Prods. Inc. v. Iancu, 933 F.3d 1336, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2019)

En banc Fed. Cir. extends § 112(f) (formerly ¶6); reverses panel decision of validity (posted 06/17/15)

In Williamson v. Citrix, aka Williamson II, the en banc Federal Circuit holds that a claim limitation reading, “distributed control module” invokes 35 U.S.C. § 112(f) (formerly ¶6) means+function analysis.

Precedent overturned

This ruling reverses the prior panel decision that found the opposite. More specifically, the court reversed previous precedent that held that absence of the word “means” created a strong presumption not to interpret the claim as a means+function claim under 35 U.S.C. § 112(f)/¶6.

New holdings

The Williamson en banc court held:

- . . . such a “heightened burden” is unjustified . . . [;] we should abandon characterizing as “strong” the presumption that a limitation lacking the word “means” is not subject to § 112, para. 6. That characterization . . . has the inappropriate practical effect of placing a thumb on what should otherwise be a balanced analytical scale. It has . . . resulted in a proliferation of functional claiming untethered to § 112, para. 6 and free of the strictures set forth in the statute. Henceforth we will apply the presumption as we have done prior to Lighting World, without requiring any heightened evidentiary showing and expressly overrule the characterization of that presumption as “strong.”

- We also overrule the strict requirement of “a showing that the limitation essentially is devoid of anything that can be construed as structure.”

- The standard is whether the words of the claim are understood by persons of ordinary skill in the art to have a sufficiently definite meaning as the name for structure.

Analysis of facts

The court construed the claim limitation, distributed learning control module for receiving communications transmitted between the presenter and the audience member computer systems and for relaying the communications to an intended receiving computer system and for coordinating the operation of the streaming data module and held:

- the limitation “is in a format consistent with traditional means-plus-function claim limitations. It replaces the term 'means' with the term 'module' and recites three functions formed by the 'distributed learning control module.'”

- ”'Module' is a well-known nonce word that can operate as a substitute for 'means' in context of § 112, para. 6. [. . .] Generic terms such as 'mechanism,' 'element,' 'device,' and other nonce words that reflect nothing more than verbal constructs may be used in a claim in a manner that is tantamount to using the word 'means' because they typically do not connote sufficiently definite structure and therefore may invoke § 112, para. 6” (internal citations and quotes removed).

- The word “module” is a nonce word that “sets for the same black box recitation of structure for providing the same specified function as if the term 'means' had been used.”

- “The prefix 'distributed learning control' does not impart structure into the term 'module.' These words do not describe a sufficiently definite structure. . . . the written description fails to impart any structure significance to the term.”

Newman's dissent

Letting Newman's words speak for themselves:

I respectfully dissent from the en banc ruling that is inserted into this panel opinion at Section II.C.1. The court en banc changes the law and practice of 35 U.S.C. § 112 paragraph 6, by eliminating the statutory signal of the word “means.” The purpose of this change, the benefit, is obscure. The result, however, is clear: additional uncertainty of the patent grant, confusion in its interpretation, invitation to litigation, and disincentive to patent-based innovation.

Curiously, the court acknowledges that it “has long recognized the importance of the presence or absence of the word 'means.'” Maj. Op. at 13. Nonetheless, the court rejects the meaning and usage of “means” to signal means-plus-function claim construction. The court now overrules dozens of cases referring to a “strong presumption” of means-plus-function usage, and goes to the opposite extreme, holding that this court will create such usage from ”[g]eneric terms such as 'mechanism,' 'element,' 'device,' and other nonce words.“ Maj. Op. at 17. In the case before us, the so-called “nonce” word is “module.” Thus the court erases the statutory text, and holds that no one will know whether a patentee intended means-plus-function claiming until this court tells us.

I dissent from the majority's reasoning and the majority's holding that “distributed learning control module” falls under paragraph 6. I express no opinion on the ultimate validity of the claim; the claim must stand or fall on its merit, but does not fall under paragraph 6.

Notes

Means Plus Function limits claim to disclosed embodiments (02/08/12)

Means+FUnction: In Mettler-Toledo, Inc. v. B-Tek Scales, LLC, Judge Moore held that a claim limitation in patent 4,815,547 to “means for producing digital representations of loads applied to said counterforce” and other means plus function limitations relate to the “multiple slope integrating A/D converter” described in the sole embodiment of the patent application, and equivalents thereof. The accused product has a delta-sigma A/D converter, not a multiple slope A/D converter, and the jury determined that there was neither literal infringement or infringement under the doctrine of equivalents. A statement in the abstract generically referencing an A/D converter cannot be relied upon as a disclosure of a generic A/D converter where the written description consistently references only a multiple slope A/D converter.

Obviousness: The jury returned a verdict that patent 4,804,052 was obvious, and a motion for judgment as a matter of law (JMOL) to reverse the jury was denied. Defendant/Appellants argue that prior art reference, GB 1,462,808 (“Avery”) does not teach correcting for load position on the scale, whereas each of the independent claims require this feature. The Court finds in favor of Plaintiff/Appellee becuase it found “substantial evidence [to support] the jury determination….”

"Mechanism" + function triggers 112 ¶6; linear not equiv. to rotational; Distinction between DoE and structural equiv. under ¶6 (12/16/08)

In Welker Bearing Co. v. PHD, Inc., the Fed Cir. upheld the district court's summary judgment ruling that a limitation in Welker Bearing's patent should be interpreted as a means plus function limitation under 35 U.S.C. § 112, paragraph six. Specifically, the court noted, “No adjective endows the claimed 'mechanism' with a physical or structural component. Further, claim 1 provides no structure context for determining the characteristics of the 'mechanism' other than to describe its function. Thus, the unadorned term, . . . is simply a substitute for the term 'means for'” (quoting Lighting World2). Furthermore, the Fed. Cir. agreed with the district court's finding that the specification only mentions “rotating” and therefore PHD's product's linear actuator does not infrigne because it is not equivalent to the rotating post described in the specification.

In Welker Bearing Co. v. PHD, Inc., the Fed Cir. upheld the district court's summary judgment ruling that a limitation in Welker Bearing's patent should be interpreted as a means plus function limitation under 35 U.S.C. § 112, paragraph six. Specifically, the court noted, “No adjective endows the claimed 'mechanism' with a physical or structural component. Further, claim 1 provides no structure context for determining the characteristics of the 'mechanism' other than to describe its function. Thus, the unadorned term, . . . is simply a substitute for the term 'means for'” (quoting Lighting World2). Furthermore, the Fed. Cir. agreed with the district court's finding that the specification only mentions “rotating” and therefore PHD's product's linear actuator does not infrigne because it is not equivalent to the rotating post described in the specification.

Doctrine of Equivalence: As pointed out in Hal Wegner's post, this case highlights an important difference between structural equivalents under 35 USC § 112, ¶ 6 and the doctrine of equivalents. Quoting Al-Site Corp. v. VSI Int'l, Inc., 3), this distinction ”'involves the timing of the … analyses for an ‘insubstantial change.' . Namely, an equivalent structure under § 112 ¶ 6 'must have been available at the time of the issuance of the claim,' whereas the doctrine of equivalents can capture after-arising 'technology developed after the issuance of the patent.' Id.“

- Patents in suit: 6,786,578 and 6,913,254.

General purpose CPU or processor insufficient structure under §112-¶6 (04/04/08)

In Aristocrat v. IGT, 521 F.3d 1328, 86 U.S.P.Q.2d 1235 (2008), the Fed. Cir. held that the trial court committed no reversible error in its summary judgment that all claims of Aristocrat's patent are invalid under 35 U.S.C. §112, sixth paragraph. Specifically, the trial court held that the patent lacked sufficient structure to support claim limitations for “game control means.” The court stated “there was no adequate disclosure of structure in the specification to perform” the functions performed by the game control means. Stated the court (citing WMS Gaming, 184 F.3d at 1348): in a means-plus-function claim “in which the disclosed structure is a computer, or microprocessor, programmed to carry out an algorithm, the disclosed structure is not the general purpose computer, but rather the special purpose computer programmed to perform the disclosed algorithm.” Furthermore, “language [that] simply describes the function to be performed, [is] not the algorithm by which it is performed.” It is insufficient and contrary to Fed. Cir. precedent that an algorithm to perform that function is within the capability of one of skill in the art.

- Patent in suit: 6,093,102

M+F claims not fully enabled; ATI impacted (09/09/07)

In ATI v. major automakers, a claim limitation reading ”(c) means responsive to the motion of said mass upon acceleration of said housing in excess of a predetermined threshold value, for initiating an occupant protection apparatus“ brought trouble for patent holder ATI due to a poorly written specification. The specification addressed a mechanical acceleration sensor having a moving body that engages electrical contacts, as well as a conceptional electronic embodiment in which movement of the body “can be sensed by a variety of technologies using, for example, optics, resistance change, capacitance change or magnetic reluctance change.” Although such electronic acceleration sensors were well known, the specification states that their use for automotive side impact airbags is unknown, and the defendants managed to convince the court that existing knowledge of electronic acceleration sensors is not applicable, and that the specification therefore would require undue experimentation to carry out the full scope of the means plus function limitation, which includes both electrical and physical sensors.

- Analysis and commentary (cached copy)

Inadequate structure leads to indefiniteness for means+function claim (06/24/07)

In Biomedino v. Waters Technology et al., the Fed. Cir. upheld a lower court ruling that a claim limitation of “control means for automatically operating [a] valving” was indefinite under 35 U.S.C. §112, second paragraph because the application as a whole lacked sufficient structure to support the means plus function limitation, construed according to 35 U.S.C. §112, 6th paragraph.

In Biomedino v. Waters Technology et al., the Fed. Cir. upheld a lower court ruling that a claim limitation of “control means for automatically operating [a] valving” was indefinite under 35 U.S.C. §112, second paragraph because the application as a whole lacked sufficient structure to support the means plus function limitation, construed according to 35 U.S.C. §112, 6th paragraph.

- Summary

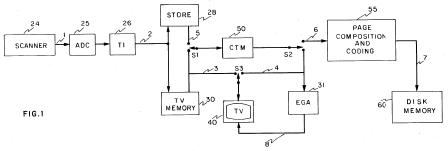

Making Copies: ''MIT v. Abacus'' (09/13/06)

In MIT v. Abacus Software Fed. Cir., Sept. 2006, MIT argued that its patent for a “scanner” included a digital camera and that “colorant selection mechanism” does not fall under §112 ¶6. MIT loses. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the scanner must have “relative movement between the scanning element and the object being scanned.” With regard to the §112 issue, the Federal Circuit noted that “The generic terms 'mechanism,' 'means,' 'element,' and 'device,' typically do not connote sufficiently definite structure.” The court, however, also found that the phrase “aesthetic correction circuitry” has “enough substance to elude the straightjacket of mean-plus-function construction.” Go figure. :)

In MIT v. Abacus Software Fed. Cir., Sept. 2006, MIT argued that its patent for a “scanner” included a digital camera and that “colorant selection mechanism” does not fall under §112 ¶6. MIT loses. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the scanner must have “relative movement between the scanning element and the object being scanned.” With regard to the §112 issue, the Federal Circuit noted that “The generic terms 'mechanism,' 'means,' 'element,' and 'device,' typically do not connote sufficiently definite structure.” The court, however, also found that the phrase “aesthetic correction circuitry” has “enough substance to elude the straightjacket of mean-plus-function construction.” Go figure. :)