Table of Contents

Validity under §112

S.Ct. upholds status quo on enablement (posted 05/25/23)

May 18, 2023: In Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, the Supreme Court unanimously held that Sanofi's “genus” patents – patents directed to broad patents cholesterol-lowering monoclonal antibodies but directed to a specific antibodies – were invalid for lacking an enabling disclosure. Stated the court: “If a patent claims an entire class of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter . . . the patent's specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class.” Because the class being claimed covers potentially millions of antibodies and the specification only describes 26 specific antibodies, the specification fails this test. The court further explained that it is not required for a patent to explain how to make and use every single embodiment within a claimed class, but should give examples along with identifying specific characteristics that would allow someone else to make and use everything that the patent claims.

This ruling is consistent with prior Federal Circuit holdings that the entire scope of a claimed invention must be enabled. See, e.g., Liebel-Flarsheim v. Medrad 1) discussed here. However, in their Yale Law Journal article, "The Antibody Patent Paradox"2) the authors Lemley and Sherkow argue that the written description requirement is inconsistent with the science of antibody research. As we can now learn more about the molecular structure through DNA sequencing, the requirements for satisfying the written description requirement has grown more stringent and is incompatible with how scientists understand antigen science.3)

“Put less abstractly, researchers have little interest in the particular DNA sequence that gives rise to a particular antibody; they are instead interested in what the antibody does and how it does it. So, although function can make an antibody representative of a class, by establishing a group of molecules according to what they bind to and how, this class might have no “common structural features.” This representative-structure standard is, if not scientifically impossible, textually impractical. Demanding it is roughly equivalent to demanding that a sofware patent identify individual strings of computer code that every implementation must have in common, even if slight variations do the exact same thing.”

On 1/10/24, the USPTO published 4) guidelines for implementing the Amgen v. Sanofi decision. The new guidelines state that the office will continue to use the framework of eight factors developed in In re Wands 5), referred to as the Wands factors to determine “reasonableness of experimentation.”

Supreme Court un-defines "definiteness" with "reasonable certainty" (updated 08/05/15)

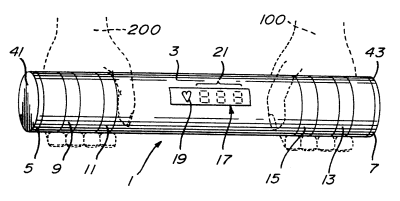

In Nautilus v. Biosig Instruments (cached), the Supreme Court vacated and remanded to the Federal Circuit its reversal and remand of the district court's conclusion that that the phrase “spaced relationship” of electrodes of a heart rate monitor was indefinite. (If the electrodes touched, then that would short the circuit, and the heart rate of a person holding the sensor could not be determined.) The Supreme Court specifically overturns Federal Circuit precedent stating that, a claim is indefinite “only when it is 'not amenable to construction' or 'insolubly ambiguous'” 6). Instead, the Supreme Court holds that § 112 ¶2 requires:

In Nautilus v. Biosig Instruments (cached), the Supreme Court vacated and remanded to the Federal Circuit its reversal and remand of the district court's conclusion that that the phrase “spaced relationship” of electrodes of a heart rate monitor was indefinite. (If the electrodes touched, then that would short the circuit, and the heart rate of a person holding the sensor could not be determined.) The Supreme Court specifically overturns Federal Circuit precedent stating that, a claim is indefinite “only when it is 'not amenable to construction' or 'insolubly ambiguous'” 6). Instead, the Supreme Court holds that § 112 ¶2 requires:

“that a patent's claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty. The definiteness requirement, so understood, mandates clarity, while recognizing that absolute precision is unattainable. The standard we adopt accords with opinions of this Court stating that “the certainty which the law requires in patents is not greater than is reasonable, having regard for their subject matter.” [Citations omitted].”

Remand from Supreme Court

On remand from the Supreme Court, in a separate opinion, the Federal Circuit reviewed the Supreme Court's decision, prior case law related to “reasonable certainty,” and the factual record relied upon in their initial decision to find that Biosig's claims satisfy 112 ¶2, and again held that the claims are not indefinite.

- Federal Circuit's Oral Arguments on Remand recorded January 7, 2015.

A petition for en banc review was later denied.

- Discussion and highlights

Claim scope narrowed by spec; invalidated by §112, ¶1 (03/16/09)

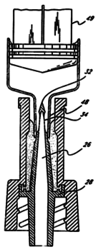

In ICU Medical v. Alaris Medical Systems, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the district court's narrow construction of the term, “spike” as being “an elongated structure having a pointed tip for piercing the seal, which tip may be sharp or slightly rounded” stating that “it is 'entirely proper to consider the functions of an invention in seeking to determine the meaning of particular claim language.'” 7)

§112, ¶1: In addition, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the district court's finding of invalidity under §112 ¶1 of broader “spikeless” claims. The Fed. Cir. cited LizardTech v. Earth Resource Mapping 8) and rejected ICU's contention that “a person . . . would recognize that the specification discloses a preslit (or precut) seal that would permit fluid transmission without the piercing of a spike.” Stated the court: “It is not enough that it would have been obvious . . . that a preslit trampoline seal could be used without a spike. ICU has failed to point to any disclosure in the patent specification that describes a spikeless valve with a preslit trampoline seal” (citation omitted).

Cross posted: Claim Construction

Fed. Cir. finds "fragile" vague (01/27/07)

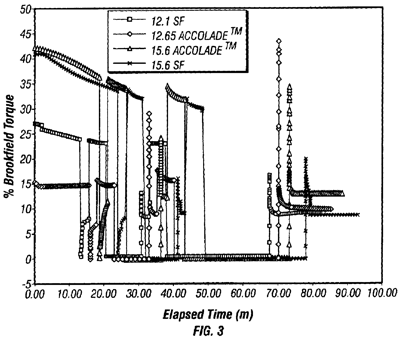

In Halliburton Energy Services, Inc. v. M-I LLC, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the district court's grant of summary judgment, agreeing that the term “fragile gel” is not amenable to construction or insolubly ambiguous and therefore indefinite (citing Datamize, LLC v. Plumtree Software, Inc. 9). The Fed. Cir. rejected Halliburton's arguments that a fragile gel is one that easily transitions from gel to liquid and back again is sufficiently objective so that a skilled artisan would understand the scope. Halliburton's suggestion that the “L-shaped” curve exhibited by a Brookfield viscometer shown in Figure 3 of the patent (reproduced here) identifies a fluid as being a “fragile gel” as rejected because, as Halliburton admits, the prior art 12.1 SF fluid also exhibits this feature. The Fed. Cir. also rejected Halliburton's arguments that fragile gel is defined as a gel that can suspend drill cuttings and weighting materials at rest because the quantity, weight, size and/or volume of cuttings to be suspended was undefined. The Fed. Cir. drew a parallel between this argument and that presented Geneva Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. GlaxoSmithKline PLC, 10) regarding the phrase, “synergistically effective amount,” stating that in the present case, “an artisan would not know from one well to the next whether a certain drilling fluid was within the scope of the claims because a wide variety of factors could affect the adequacy.”

In Halliburton Energy Services, Inc. v. M-I LLC, the Fed. Cir. affirmed the district court's grant of summary judgment, agreeing that the term “fragile gel” is not amenable to construction or insolubly ambiguous and therefore indefinite (citing Datamize, LLC v. Plumtree Software, Inc. 9). The Fed. Cir. rejected Halliburton's arguments that a fragile gel is one that easily transitions from gel to liquid and back again is sufficiently objective so that a skilled artisan would understand the scope. Halliburton's suggestion that the “L-shaped” curve exhibited by a Brookfield viscometer shown in Figure 3 of the patent (reproduced here) identifies a fluid as being a “fragile gel” as rejected because, as Halliburton admits, the prior art 12.1 SF fluid also exhibits this feature. The Fed. Cir. also rejected Halliburton's arguments that fragile gel is defined as a gel that can suspend drill cuttings and weighting materials at rest because the quantity, weight, size and/or volume of cuttings to be suspended was undefined. The Fed. Cir. drew a parallel between this argument and that presented Geneva Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. GlaxoSmithKline PLC, 10) regarding the phrase, “synergistically effective amount,” stating that in the present case, “an artisan would not know from one well to the next whether a certain drilling fluid was within the scope of the claims because a wide variety of factors could affect the adequacy.”

Intersection of §112 2¶2 validity and §102 anticipation: In response to Halliburton's arguments that a determination of whether the claim reads on the prior art 12.1 SF fluid should be reserved for a validity analysis under §102, the Fed. Cir. disagreed, holding that a evaluation of a claim's definiteness can include a determination as to whether the patent expressly or at least clearly differentiates itself from specific prior art. Stated the court: “Such differentiation is an important consideration in the definiteness inquiry because in attempting to define a claim term, a person of ordinary skill is likely to conclude that the definition does not encompass that which is expressly distinguished as prior art.”

Functional claim limitations: The Fed. Cir. gave the following advice when dealing with functional claim limitations:

When a claim limitation is defined in purely functional terms, the task of determining whether that limitation is sufficiently definite is a difficult one that is highly dependent on context (e.g., the disclosure in the specification and the knowledge of a person of ordinary skill in the relevant art area). We note that the patent drafter is in the best position to resolve the ambiguity in the patent claims, and it is highly desirable that patent examiners demand that applicants do so in appropriate circumstances so that the patent can be amended during prosecution rather than attempting to resolve the ambiguity in litigation.

A patent drafter could resolve the ambiguities of a functional limitation in a number of ways. For example, the ambiguity might be resolved by using a quantitative metric (e.g., numeric limitation as to a physical property) rather than a qualitative functional feature. The claim term might also be sufficiently definite if the specification provided a formula for calculating a property along with examples that meet the claim limitation and examples that do not. See Oakley, Inc. v. Sunglass Hut Int’l, 316 F.3d 1331, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

An additional blurb on this case is provided in the procedural matters section.

- Patent in suit: 6,887,832

Patent must enable "full scope of the claims" (03/22/07)

In Liebel-Flarsheim v. Medrad 11), the Fed. Cir. held that claims are not enabled even though a preferred embodiment is clearly enabled if the claims also read on non-enabled embodiments, in particular where the non-enabled embodiments requires a significant amount of experimentation to practice the non-enabled embodiment as evidenced by the specification teaching away from the non-enabled embodiments. The court distinguished Spectra-Physics noting that, while the court invalidated the claims in that case based on best mode but found a single disclosed attachment technique was sufficient to enable other attachment techniques within the scope of the claims, the other attachment techniques were well known in the art. With regard to a second claim asserted by Liebel, the court found the broad interpretation asserted by Liebel, which the Fed. Cir., in an earlier decision agreed with, was anticipated by an earlier patent by Medrad.

- Analysis and commentary (cached copy)

Claim invalidated under 35 U.S.C. §112 ¶4 (08/03/06)

In Pfizer, Inc., et al. v. Ranbaxy Laboratories, Limited, et al., Pfizer asserts claim 6, reading, “The hemicalcium salt of the compound of claim 2.” The court noted that 35 U.S.C. §112 4 states:

“Subject to the following paragraph [concerning multiple dependent claims], a claim in dependent form shall contain a reference to a claim previously set forth and then specify a further limitation of the subject matter claimed. A claim in dependent form shall be construed to incorporate by reference all the limitations of the claim to which it refers.”

Stated the court: Ranbaxy correctly argues that claim 6 fails to “specify a further limitation of the subject matter” of the claim to which it refers because it is completely outside the scope of claim 2. We must therefore reverse the district court with respect to this issue and hold claim 6 invalid for failure to comply with § 112, 4.“